Piedmont Virginia, like the rest of the Piedmont south, bakes in the summer under long dry spells, suffocates in humidity, and hosts violent storms coming off the Gulf, the Atlantic, and the Monongahela. It’s a brutal, fertile, heartbreaking climate where trouble can blow in from any direction, though insects and things that eat insects seem to love it. The ancestors had to battle the July sun. They did not get to sit in a shady arbor with a bit of breeze and something chilled and bubbly. If they had thrown in the sponge on summer, none of us would be here and the Raccoon would be the dominant species on earth.

These are days of danger for the gardener. Heat stroke is not a conspiracy theory, and even incipient heat stroke can ruin your week. We pop out in the early morning and do what we can before the sun takes over. Younger gardeners can do more. Older gardeners are obliged to do less. Something I’d consider a warm-up task in October or May—some little job to finish before putting in a full day—turns into all I can do for the day, in July. The air seems hot and sticky, even syrupy. You are bitten, scratched, crawled on. There are poisons concealed in the most innocent places. Brushing against a tiny Saddleback caterpillar on the underside of a leaf (the likeliest place to find one is the out-of-view underside) is about equivalent to a hornet sting or, if you’re lucky, a really full-on sting from a red wasp. The Spiny Oak Slug is a good deal worse. The Buck Moth caterpillar, also an oak caterpillar, is just about common here and a run-in with one will put an end to the day. Sometimes in July, all that really makes sense for a gardener to do is to go inside and let the neurotoxins burn themselves out while the swelling goes down. C’est la guerre.

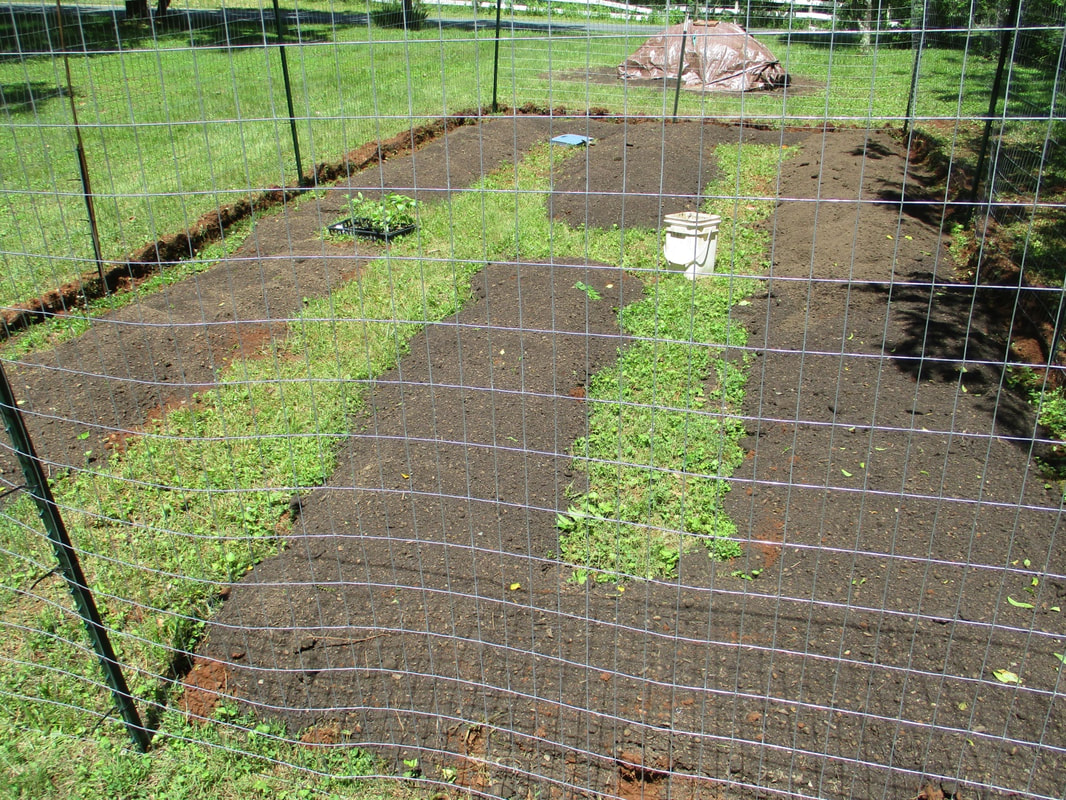

Both the ornamental and the vegetable garden have been showier and more productive in 2020 than ever before. This is largely because the pandemic is keeping us home. Karen now has time to go through the individual vegetable plants nearly every day, picking eggs, larvae and destructive pests off by hand. The hand-picking technique is a bit prehistoric but we can see that it works fairly well, time and energy allowing.

Doctors and druggists ordinarily compounded with acutely poisonous medicinal plant materials in Hawthorne’s time. Herbalists’ gardens and medical gardens of biologically active plants would not have seemed entirely strange in 1844 and a secret poisonous garden is not an enormously exaggerated possibility. There would have been herbalists with plant collections in the Boston area. There were important medical gardens in Padua, whose university has been at the forefront of Western science since 1222. By romanticizing an equally poisonous secret girl, Rappaccini’s Daughter joined the tradition of desperately doomed Italian love affairs, a tradition including Shakespeare and Boccaccio and probably the Etruscans.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed