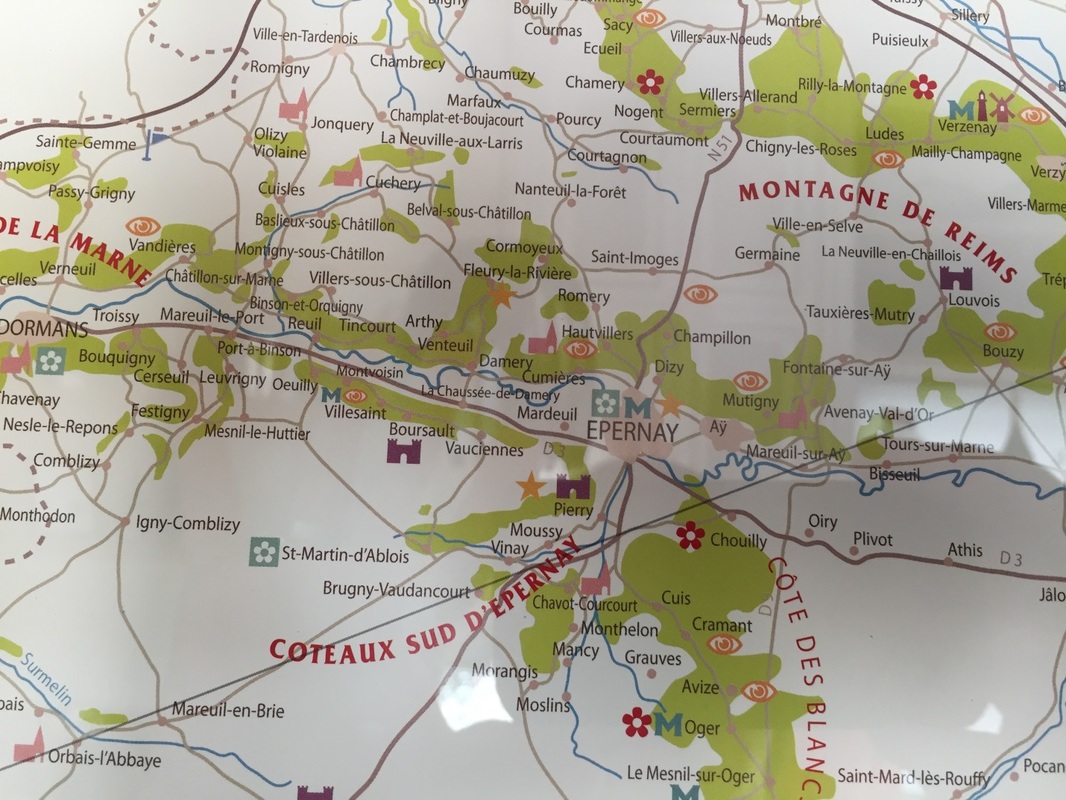

At the end of my previous post we were leaving Reims. Meandering down side roads through forets full of renards, we headed toward Epernay.

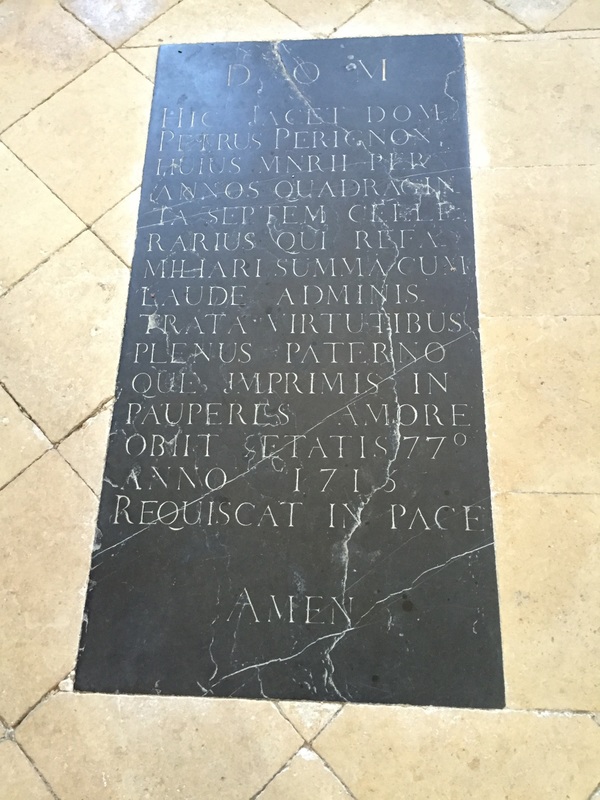

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dom_P%C3%A9rignon_%28monk%29

As Tacitus once noted, success has a hundred fathers but failure is an orphan. Bubbly wine is prehistoric, but technology was needed for bubbly wine to become champagne, including the invention of thicker bottles to reduce the risk of explosion, a development that came after Perignon’s time. Perignon’s contributions seem to have been taste, method and planning; in effect, the ability to control the fermentation reactions, the ancestral Méthode Champenoise itself. As a refiner of existing techniques, Dom Perignon should be the patron saint of editors. The official patron saint of editors, Saint Bosco, is weirdly shared as the patron saint of chocolate syrup. To the Pope I say, “Please let us have Dom Perignon instead.” Perignon’s miracles have always been obvious, even to nonbelievers.

The Abbey of Hautvillers is modest, charming, and musty.

Relic veneration was no transient mania. Hundreds of years after Helena, historians recorded the return of the survivors of the First Crusade to their native cities in Northern France and Flanders — bands of sunburnt and bearded warriors garbed in oriental robes, carrying in their luggage an incalculable wealth of mummified heads, petrified hearts and other organs, femurs, teeth, finger bones, toe bones, the original spear stuck into Jesus on the cross, and anything else of the kind they had uncovered. But the real tsunami of holy relics came after the fall and sack of Constantinople in the Fourth Crusade, on April 12, 1204 CE, a date that will live in infamy. Before then, Crusaders had to be content with things St. Helena did not find first. But in 1204 her whole vast collection, which included most of the True Cross, all the Holy Family’s next-of-kin, and several entire disciples, was carried off to Western Europe — and her own sacred remains too, looted along with the rest. Such a supernaturally exquisite irony deserves more than one toast in the best possible champagne. Sometimes history actually makes perfect sense.

On to Epernay.

I remember Epernay as quite lively – that is, everyone we met was vivacious — but objectively Epernay was not at all crowded.

Châlons, down the traditional invasion route from Epernay, shares in common with a lot of Northern French towns what a science fiction writer might call “The Armentieres Paradox.” No doubt there is a modern Châlons with 3 or 4 Starbucks locations and a row of fine restaurants near the university, a couple of multiplex theaters and several streets for boutique shopping, three or four well-heeled suburbs, and an outer ring of malls and car dealerships. But we never saw this side of France, not in Armentieres and not in Châlons. Instead we invariably drove to some dominant gothic spire and parked.

Châlons has two of these stupendous monuments. The first we encountered was Notre-Dame-en-Vaux, stuffed into a modern vehicular intersection like the stake in a vampire’s heart. We were late in the day and the basilica was closed, and we were very, very sorry, because this was no medieval afterthought. It was a ship-of-the-line among basilicas, its construction having begun in 1157 and finished in 1217.

We walked toward the Grand Place and the cathedral. Châlons was successfully old. It desperately calls for a closer look.

Châlons, or at least this part of it, closed before sunset, except for the astonishing revels of a squad of French Marines, their girlfriends and some hangers-on at the only café that was still open in the Grand Place. Whatever we had to drink was unmemorable and too warm, and we quickly realized the kitchen staff was consumed by the Rabelaisian task of keeping the Marines supplied; it would take hours for us to be served. We left.

We had reservations in the basically nonexistent village of Marre, 12 km from Verdun. That was why we had come to France in the first place. It was time to go there.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed