Our plan for the next day was to explore the eastern end of the Argonne Forest battlefield. We would be following, by car, the route taken by Frank Wolinski, Karen’s maternal grandfather and Alex’s great-grandfather, who as a sergeant in Company C of the 47th Infantry Regiment went over the top in the first wave of the attack on the Argonne Forest on September 26, 1918.

Years ago, I wrote an essay on Frank Wolinski’s experiences in the Great War. Frank Wolinski participated in all three American campaigns, was decorated twice and promoted to platoon sergeant, and then took part in the occupation of Germany, returning home in the summer of 1919. My original essay was a response to a family request and too quick a job, but everyone was very kind and no one complained. The subject however is a good one, and since Alex and I were in France, here was a clear opportunity to visit some of the scenes and rewrite the essay.

| For my newly published narrative on Frank Wolinski's experiences during the Great War, click here. |

British and European histories regard the Battle of the Argonne Forest as one of several huge offensives in late 1918 that liberated German-occupied France, collectively destroyed the ability of the German Heer to defend the borders of Germany, and led to the Armistice on November 11, 1918 and the Treaty of Versailles the following year. In an exchange of letters with General John Pershing after the war, Marshal Ferdinand Foch suggested that all the offensives composed one continuous battle, which he suggested could be called the Battle of France. By another reckoning, British historians tended to consider the Second Battle of Cambrai in early October 1918 and the dissolution of parts of the German defense lines in northern France as the death-knell of the German position on the Western Front. Objectively it is reasonable to say the whole front was collapsing from the English Channel to the Alps, at a terrible cost to all sides.

Americans tended, for a time, to view the Battle of the Argonne Forest as the unique killing stroke that ended the war. It had been the largest battle in American history by far, and like other Great War battles seemed calculated to boggle the imagination and defy description. The scale of American losses was likewise staggering. From the U.S. perspective, the Battle of the Argonne Forest seemed truly singular. President Wilson’s triumphant imperial reception in Europe after the Armistice, when the heads of the victorious nations met to redraw the map of the world, strengthened the sense that the Argonne Forest was the climax of the War to End all Wars and a decisive battle that changed world history forever.

American travelers returned to Europe in droves in 1919 and 1920, and for a time the Argonne Forest battlefield was high on the tourist agenda. It was a famous place, and the huge American military cemetery next to Montfaucon was a pilgrimage site for countless mourners. The tourists and the mourners brought back lots of fresh unrusted debris which can be found in many a Great War militaria collection today. A number of monuments were commissioned, including the magnificent Art Deco eagle gates at the main American cemetery, and the American Memorial Tower on Montfaucon, mate to the Verdun lighthouse just out of sight in the distance beyond Le Morte Homme.

But before these monuments could be finished, the nation lost interest in the war. By the time the last U.S. occupation troops returned from the Rhineland in 1923, Wilson was gone and the parades were over. The country had already shrugged off Wilson’s League of Nations, the Fourteen Points, and Wilson’s definition of progress. The war had become, not exactly an embarrassment, but something no longer convenient to examine closely. Veterans’ relief organizations and the divisional associations petered out of existence, or turned into reunion clubs, and the Great War passed from historical climax to old news while the commemorative marbles were still being carved.

Nothing has occurred since to reverse the early wave of disinterest that pigeonholed the American phase of the Great War as a historical curiosity. The facts of the war had been a nasty shock to American idealism. The Allied diplomats were the first to turn their backs on Wilson at Versailles, rejecting the President’s plea that peace without justice would be no peace at all. Instead the Versailles Treaty became a poisonous brew, about vengeance on Germany more than anything else, though also ignoring the interests of some of the Allied nations as well, notably Japan, while fractionalizing Central Europe and the former Ottoman Empire, acts whose repercussions are very much with us today, and ignoring the claims of colonized and enslaved peoples everywhere. Then, after the world rejected the Fourteen Points, Wilson returned home to find the United States rejecting the League of Nations. Americans generally speaking now wanted to put the whole episode behind them.

Wilson’s defeat was a world tragedy then and remains a tragedy now. Some might say it is not too late—would still be surprisingly timely—to dig out the Fourteen Points and try all fourteen of them. Over a hundred thousand Americans died for that and lie in France today, dream unfulfilled. More than two hundred thousand were injured.

Nonetheless, there was something to the original public sense that the climactic battle of General Pershing’s American Expeditionary Force was historically singular and exceptional. A century later, the Argonne Forest is still the largest land battle in American history and may remain so forever. War itself is no longer done that way. The scale of its fury also remains unmatched; the Argonne Forest concentrated as many American casualties into six weeks as the Vietnam War did in ten years.

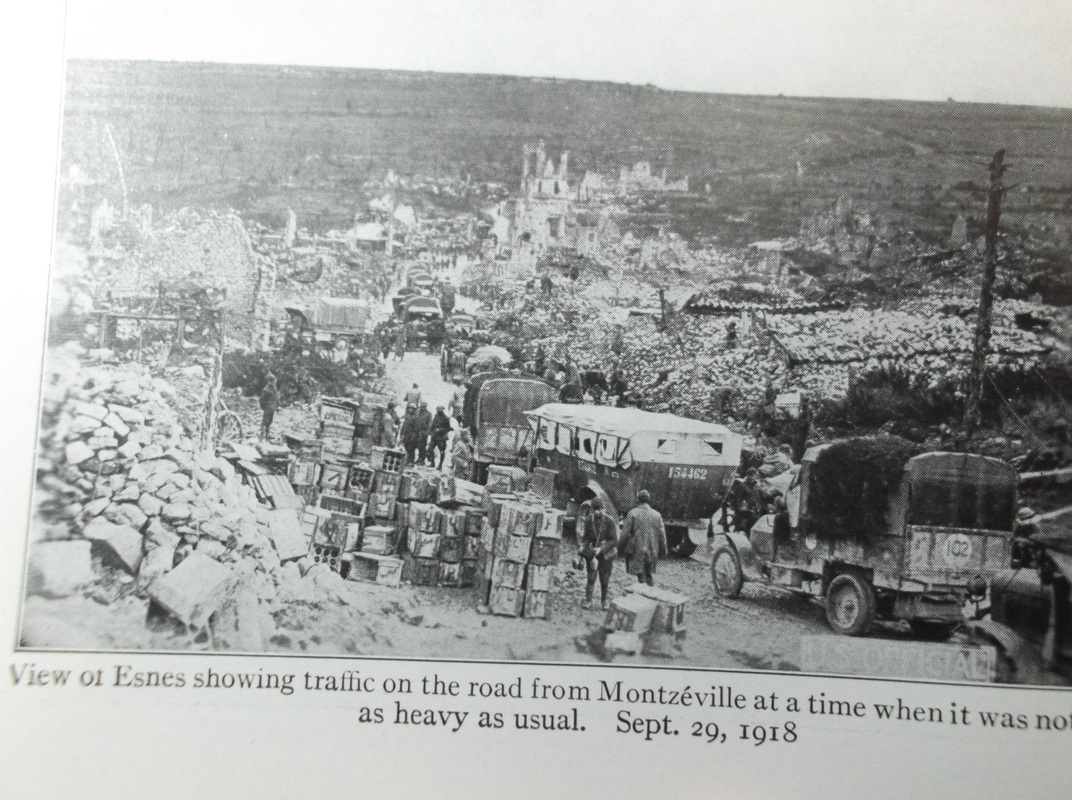

The road through Esnes is beautiful today, though deserted.

It would be possible and in fact easy to walk the track of the 47th Regiment’s advance from Hill 304 to its terminus at Brieulles-sur-Meuse. A forest service jeep trail on Hill 304 connects with the secondary roads that meander toward Nantillois. We were driving, however, and D18 goes to Malancourt on the 79th (Cross of Lorraine) Division’s line of advance.

The map link on the Brieulles website, expanded and converted to satellite view, shows the terrain.

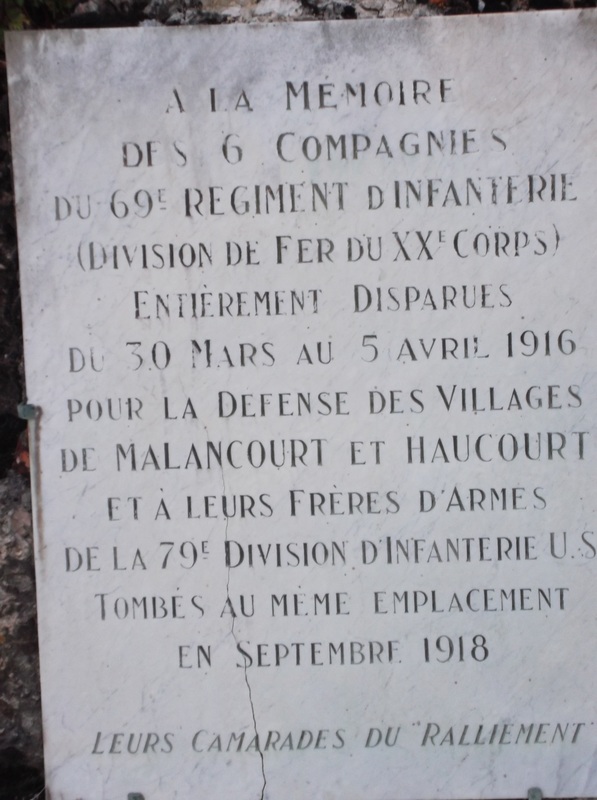

Malancourt has a remarkable memorial recording that in 1918 an American division was destroyed on the exact same spot a French regiment was destroyed in 1916—the spot in question being Montfaucon.

D168 goes to Béthincourt at the foot of Le Mort Homme, in the center of the 80th (Blue Ridge) Division’s line of advance. However, just before one reaches Bethincourt there is an unpaved road to Cuisy, angling across the 4th Division sector perfectly.

We moderns civilians also tend to forget (if we ever knew) how infantry weapons and artillery actually work. There is a tendency to mentally condense the landscape to Hollywood proportions, but on the battlefield 500 yards is well within lethal range, and anything you can actually see is inherently far too close.

Nowhere was this more painfully obvious than the American Cemetery. As at Ieper, as at the Somme and Verdun, here too the dead have been aesthetically collected from all over the neighborhood, rearranged, covered with fine white marble and rationalized back into some semblance of military order.

It was a long way to Waterloo, so we drove on.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed