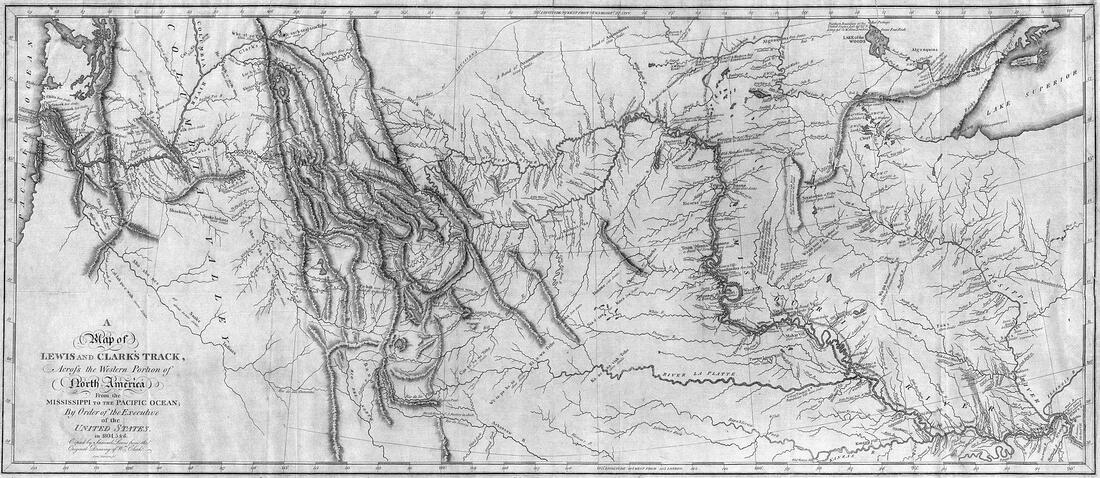

Our route picked up the trail of Lewis and Clark on the Missouri River in North Dakota, and we were repeatedly on the track of their expedition all the way to Dillon, Montana.

On their outward journey Lewis and Clark followed the Missouri into the Yellowstone near the North Dakota state line. Quite a while passed before the Rockies came into view near modern-day Billings. They were following the largest river system in North America.

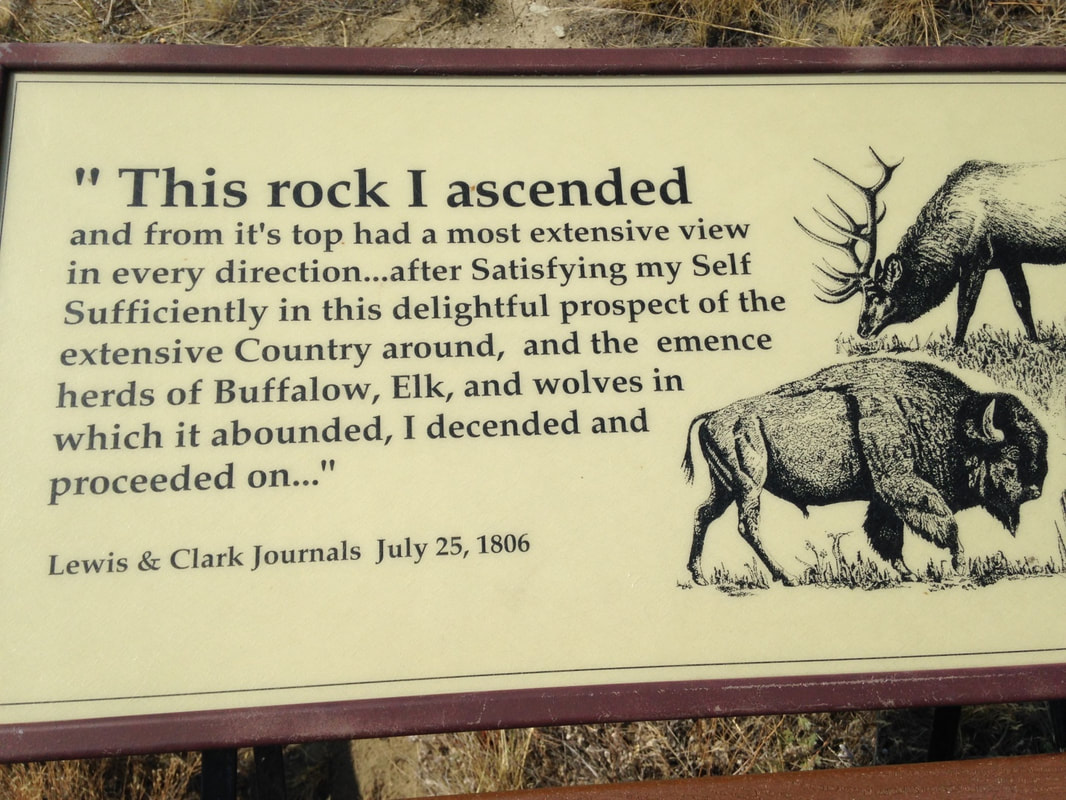

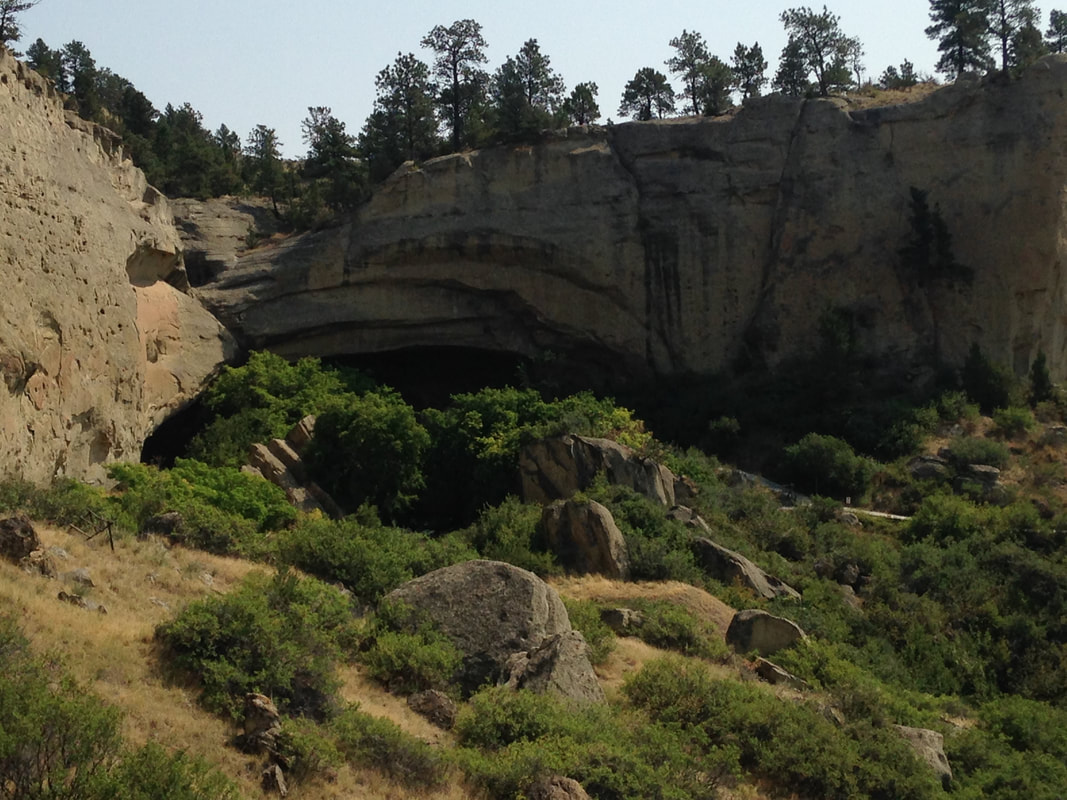

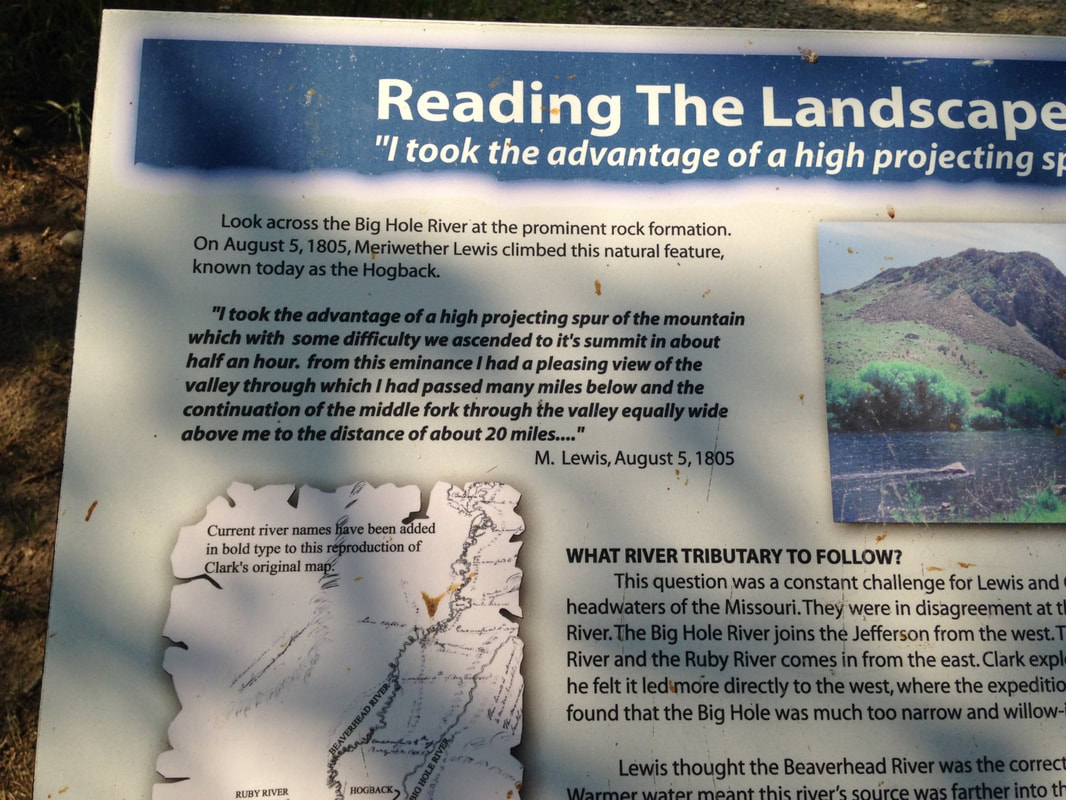

Soon they were naming various headwaters after the elusive pillars of Thomas Jefferson’s character, Wisdom, Philosophy and Philanthropy. These names did not stick, but the Native American names were also lost. The Wisdom, Philosophy and Philanthropy Rivers are the Big Hole, Willow Creek, and Ruby today. Meriwether Lewis went up the Big Hole, or Wisdom River, trying to get to the Pacific divide. This route soon lost its promise, and Lewis had to climb, to understand the real lay of the land. Soon after the Big Hole failure, Lewis and Clark chose the Beaverhead route to cross the Pacific divide.

Donnie knows these legendary trout rivers very well from his years as fishing guide working out of Dillon. Sometimes it’s valuable to go back and see the important places in your life again. Dillon, population just over 4200, did not show the fishing activity Donnie expected to see. Concerns about smoke from the fires, Covid, and drought probably affected the local trout season. Some rivers were closed to fishing. The drought is real. Covid is a disaster, and the smoke from burning California hazed out the view of the Rockies. There was fishing activity on the Madison, but basically this sport-and-tourism corner of Montana is obviously hard hit in 2021. It was interesting in Dillon and later in Virginia City to see what was closed on Mondays and Tuesdays versus Tuesdays and Wednesdays, or if the owner was working the counter from labor shortage. The sudden and near-complete loss of rental vehicles also cuts deep. To go to Dillon, you have to have something to drive. Walking remains impractical over such distances, despite the example of Lewis and Clark.

Not far from the strangely deserted trout fishing put-in where Lewis climbed the Hogback on August 5, 1805, the Nez Perce exiles stood off the U.S. cavalry for the last time at the Battle of Big Hole on August 9-10, 1877. The tragedy of the Nez Perce, driven from the Pacific Northwest onto a reservation in Idaho, then escaping into the Montana ranges in search of allies or at least a place they could defend, was the next-year sequel of the 1876 Sioux campaign. We must add this to our haunted reckoning of the Native American apocalypse.

The strategy and planning behind the 19th century cavalry campaigns in the West seem haphazard in their details. Aficionados of Civil War studies won’t recognize the same Grant and Sheridan, Crook or Custer, the same Major General O.O. Howard or Gibbon. The tactics seem clumsy, colonial, below military grade. The officers themselves thought so too—they spent much of their time making excuses for failures, casting blame, and trying to cover up grotesque mistakes. “What did they know and when did they know it” was an 1877 press meme. Somehow, corruptly, military operations in the West were a public scandal. It takes a second round of thinking to recognize that, despite the flags and the bugles, the context of these operations was not actually military. The Native Americans had already been absolutely and utterly defeated long since. The cavalry firepower was for policing reservations. Catching bands of escapees was the only strategy needed, in a pattern going back to the Dakota War in southwest Minnesota in 1862. It was already obvious that disease and numbers had settled the land tenure question.

The Plains societies collapsed like bubbles. When Lewis and Clark reached the Mandan lands in 1805, they found freshly desolated villages and a smallpox epidemic in full swing. Eastern diseases would sweep through the Plains repeatedly in the decades that followed, a pattern seen in North America since the first Spanish landings and settlements in the 1500s.

www.ndstudies.gov/gr8/content/unit-ii-time-transformation-1201-1860/lesson-4-alliances-and-conflicts/topic-1-smallpox-epidemics-1781-1837-1851/section-3-smallpox-epidemic-1837

The final fatal blow to the Plains societies—the annihilation of the bison herds—came late and seems almost unnecessary. At that point the Sioux had already been reduced to a trapped remnant But bison are dangerous and cows aren’t. Clearly settlers with cows needed the bison to go away too.

The landscape seems somewhat haunted by its historically recent human and environmental apocalypse. Facts about history are often facts about the present as well. The vast migrating herds of bison and elk were not replaced by vast herds of cows. Cows are far too expensive to risk any sort of surplus. Driving through Montana, I could not help fantasizing about putting the bison, elk and wolves back. As wild animals, they might very well support themselves, which cattle cannot do.

We approach landscapes through names. Sometimes the name we use has an older name behind it. Native American names are strewn across the landscape intermixed with settler names. Sometimes the stories explaining the settler names are as forgotten or mysterious as the Indian names, already with one foot in the world of ghosts.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed