The sun went down as our GPS sought the location of Marre.

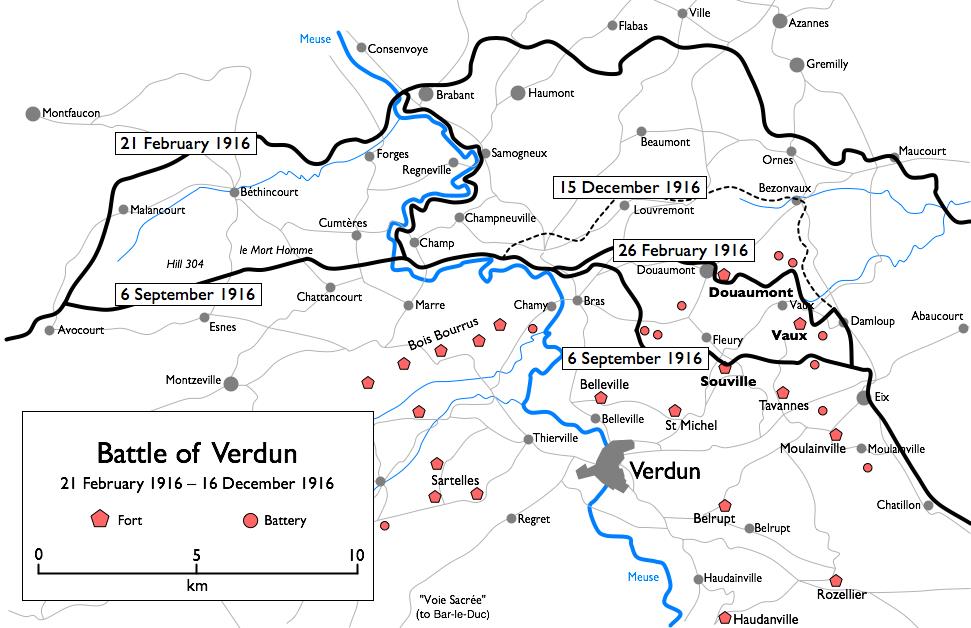

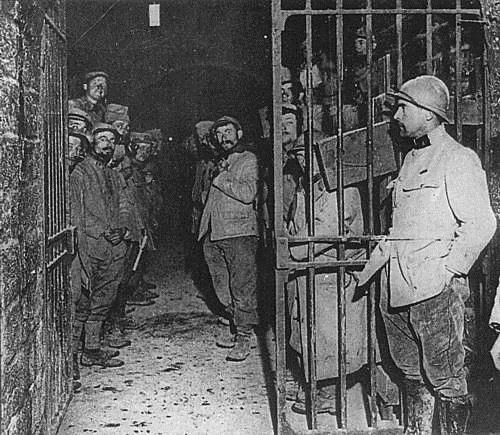

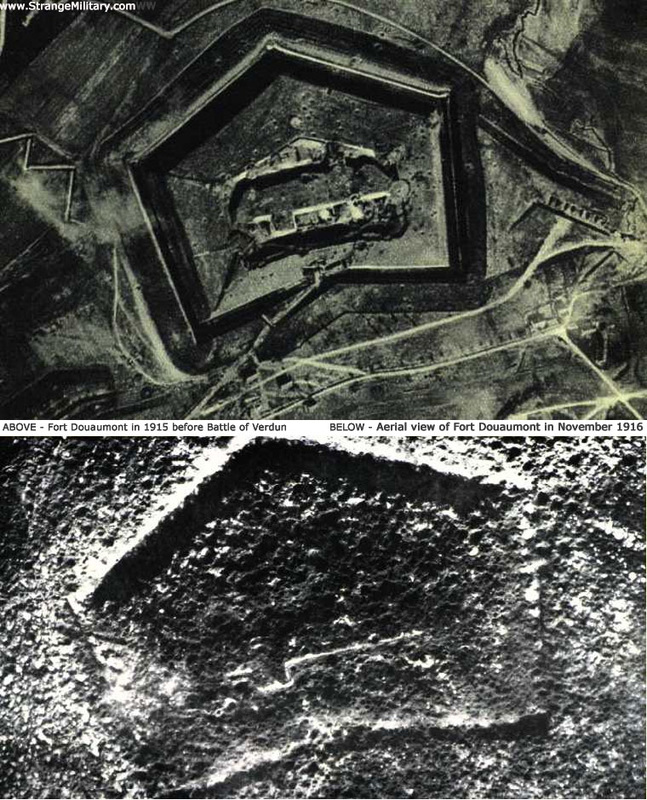

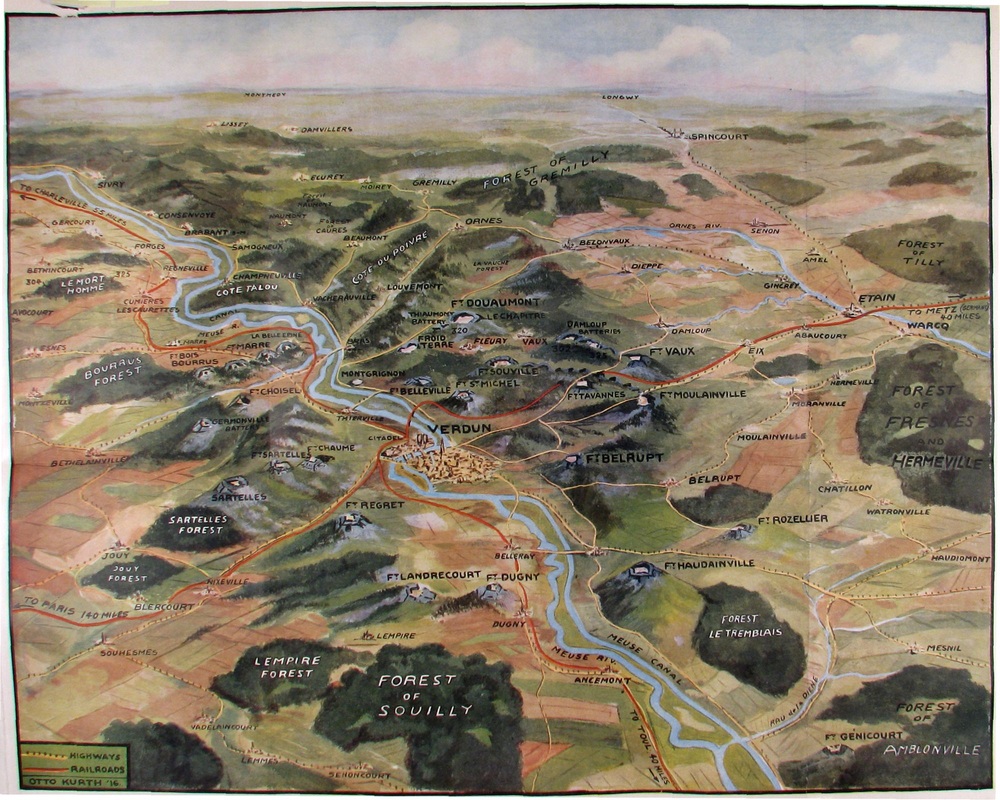

There had never been anything quite like the battle of Verdun. The ancient fortress of Verdun had been modernized over the last quarter of the 19th century to include a vast ring of underground concrete forts, marked on the map below as red pentagons. This massive feat of defensive engineering was designed to make Verdun unassailable. The fortifications, however, did not deter attack. The core battlefield at Verdun, an area of approximately 100 square miles, was quickly reduced to a landscape of overlapping shell craters. The overall battle area totals about 300 square miles, and includes many areas still infested today with unexploded shells and other ammunition, including poison gas shells. Verdun was its own planet. Western history might even be divisible into before Verdun and after, the way Americans see the Civil War. The scale of the disaster at Verdun was quickly obvious to the world at large and came to define the national nightmare of both France and Germany.

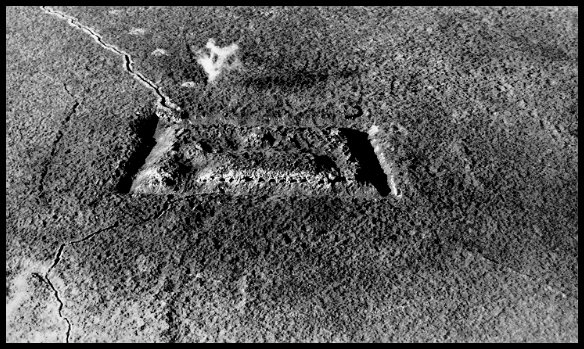

The Verdun park has lots of walking trails and back roads and on one of these we found the rear entrance to Fort Souville. After the fall of Forts Vaux and Douamont, Fort Souville and the Fleury ridgeline were for a time the center of the battle, the last obstacle for the German attack.

The whole ridge is a tumbled mass of shell holes, trenches and ruins, among which we cautiously ambled for hundreds of yards.

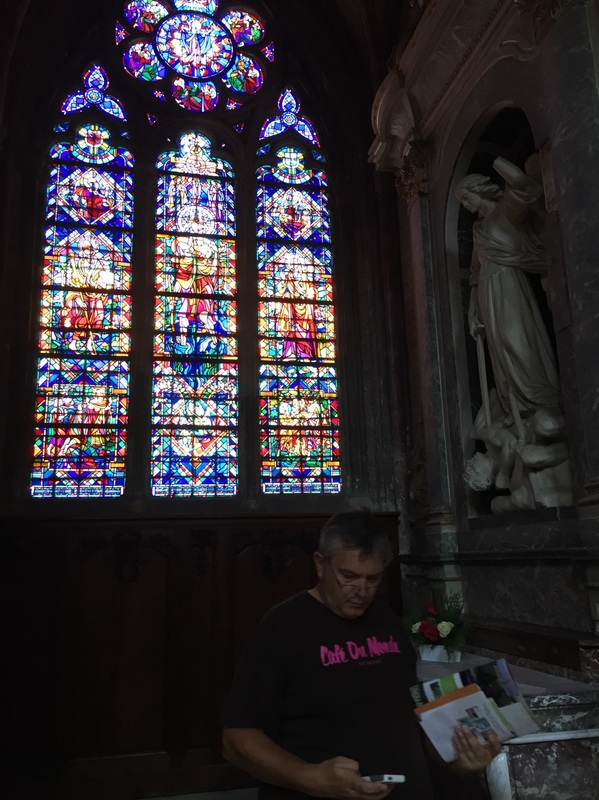

The Verdun Ossuary is a natural continuum of the medieval cathedral. While medieval cathedrals display the relics of saints, at Verdun sainthood has been democratized to include everyone. Though mostly French and German, the ossuary draws on all of Europe and the European world empire. Verdun was arguably a violent denial of liberty and fraternity, but equality was finally achieved. There is no central altar, no priestly elite, no liturgy; all were crucified, each in his own way.

At night the Ossuary Lighthouse sweeps the battlefield with its crimson beams as if to summon the angry dead. We did not stay for dark. We returned to Le Village Gaulois for an absolutely astonishing meal.

Having dined and wined very satisfactorily, we headed off to the villages detruits of Cumières, in the lee of Le Mort Homme, and Forges, at the western hinge of the 1915 front. At Forges there is signage to help indicate where things were, but there's nothing there now except trees and undergrowth slowly breaking down the shell craters. We found a dirt forest service road up onto the Mort Homme ridge that gave us a sense of the area. This fairly straight road cut through miles of superimposed trench lines from different weeks or months of the battle, riven masses of old trench snaking off in all directions through the pine plantations. As recently as the 1960s nothing but the hardiest weeds could grow on this poisoned ridge, repeatedly saturated with every form of toxic gas and chemical explosive known to either side. The pines were the first successful plantings. Late in the day we reached Le Mort Homme.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed