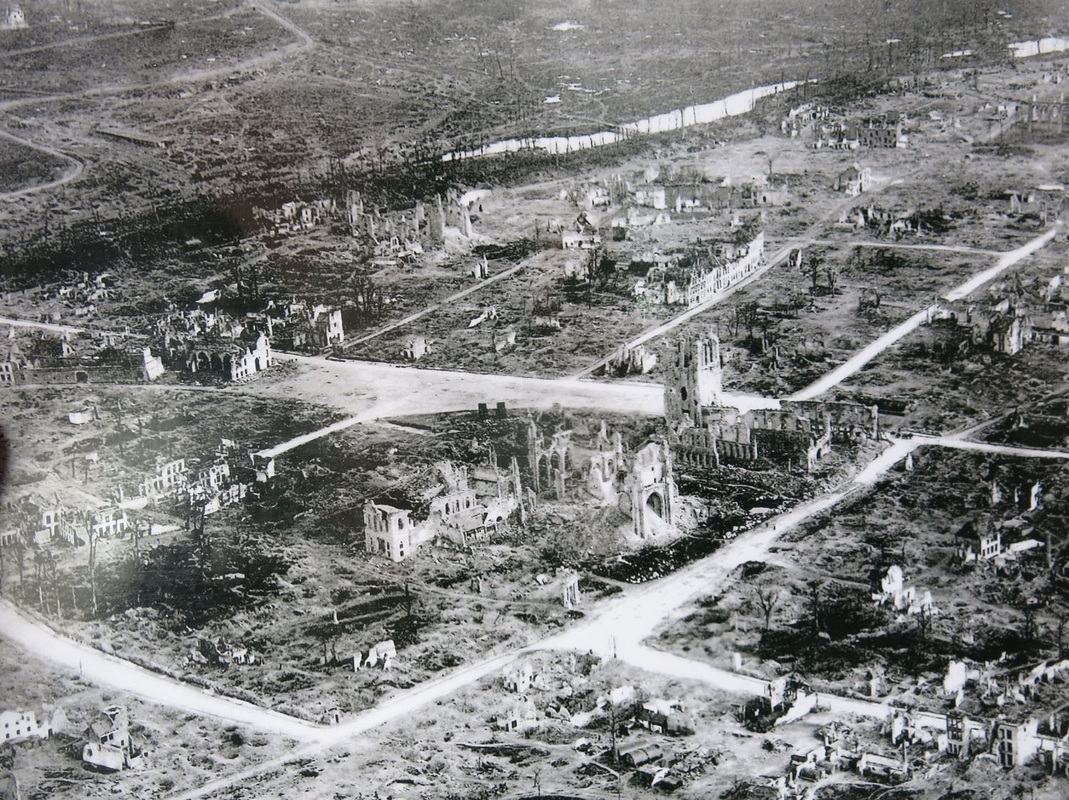

Leaving Ieper on the road to Armentières, we soon noticed more French and less Flemish in the roadside signage until the Flemish language disappeared altogether and we were in France. We intended to drive more slowly through Armentières and get a passing look at the place, and thus wandered off the high road. The somewhat quiet neighborhood in which we soon found ourselves had plainly been designed by one of the less flamboyant surrealists. Though pleasant enough in its own way, one could not help wondering where everybody had gone. Had we found the Twilight Zone? Could this be Armentières?

We mentioned to the South Africans that we were headed for Thiepval Ridge - a conversation inspired by the fact that one of them was my age and, like me, not willing to scramble over the park wall and thus obliged to go out the gate.

Rightly or wrongly, we were using the GPS in our rented Volkswagen. The South Africans in their rented Land Rover obviously decided to follow us, perhaps in the touching belief that as Americans we must already know everything. The GPS soon turned us off the main highway and onto a dirt farm lane in the vicinity of Mouquet Farm, partially blocked by farm equipment and by some French farmers vainly trying to wave us back.

I waved back too as Alex accelerated in a cloud of Somme chalk dust, the South African Land Rover right behind us. “This area is famous for the hundreds of tons of unexploded ordinance on it,” I said.

“There’s one now,” Alex said, pointing at a protective tractor tire surrounding a monstrously large artillery projectile. No doubt that was what the French farmers were on about, and the South Africans, we noticed, pulled over and stopped.

“I bet they’re trying to buy it,” I said.

I would have photographed it but Alex, with the survival instincts of a Great War ambulance driver, had the Volkswagen bounding across the ruts in a spray of gravel towards the GPS’s promise of a paved road. Perhaps the best thing.

The Thiepval memorial was roped off from visitors, shielded in scaffolding and undergoing a good cleanup in anticipation of next year’s Somme centennial. A groundskeeper on a lawn tractor was methodically towing a ground-penetrating radar set back and forth across the parking lot, searching for any leftover unexploded shells that might still be buried there. His face was serious and he was paying the most studious attention to his equipment, which made me wonder if someone with a magnetometer had perhaps come through and gotten a nasty shock.

Like the Menin Gate, the Thiepval Memorial to the Missing is a cyclopean brick-and-marble portal to the next world, bearing the names of 72,195 missing British and Commonwealth soldiers with no known grave, sometimes referred to as “the Missing of the Somme.”

See http://www.amazon.com/The-Missing-Somme-Geoff-Dyer/dp/0307742970

See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thiepval_Memorial

At the end of October, Ronald Tolkien contracted potentially lethal trench fever and was evacuated to England. He spent months in hospital and most of the rest of the war recuperating. In 1917 he wrote the first of his great literary passages, The Fall of Gondolin. By then his old company had achieved annihilation, its last handful of soldiers joining the rest of the missing.

See http://www.amazon.com/Tolkien-Great-War-Threshold-Middle-earth/dp/0618574816/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1440014543&sr=1-1&keywords=tolkien+and+the+great+war

The influence of the Great War on The Lord of the Rings and The Silmarillion can hardly be missed. The area in front of Thiepval Wood was the original Mordor, close to the German word for murder, “mord.”

And yet everything passes, and this is the face of the original Mordor today:

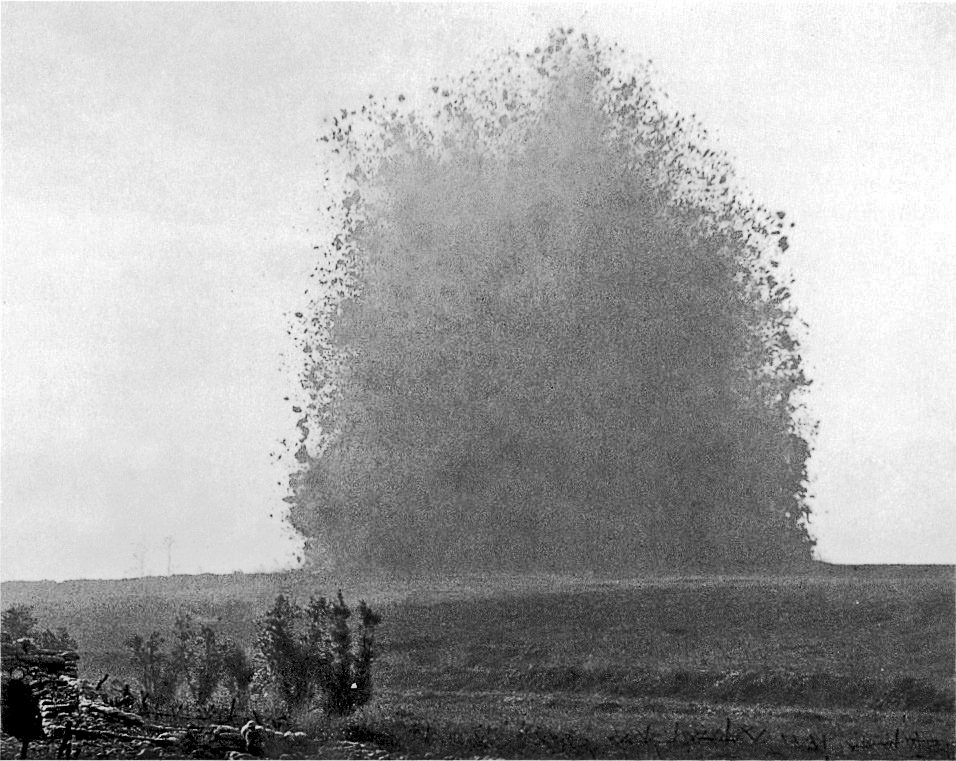

The Hawthorn Ridge mine crater was one example of the horrors the Germans faced. British engineers set off 8 large and 11 small mines under sections of the German line on the first day of the Somme. The Hawthorn Ridge explosion remains to this day one of the largest conventional explosions ever managed. Those on top of it never knew, but those around it were alerted at once that the impending attack would be on a huge scale.

(Photo by Ernest Brooks) Imperial War Museum.

In the next blog post we will turn our attention from the Great War to the great cathedrals, and from battlefields to champagne fields, before circling back to sites of conflict.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed