From Tokyo to Nikko

It’s probably worth noting that if the shogunate had not collapsed when it did, the first railroad line in 1860s Japan would have run from Edo to Nikko in one direction and from Edo to Kyoto in the other. The Nikko branch line climbing into the mountains was not luxurious or swift but had the same sense of dispatch, careful scheduling and attention to detail we soon learned to take for granted even on sleepy rural trains. The Nikko line has a

sleeping cat painted on the cars and we guessed this was a triple entendre, referring to the Shrine of the Sleeping Cat at the Tokugawa Mausoleum and also a pun on Nikko and neko.

mountains. In such places any latent tension from the woes of civilization seems to flow out of the soles of one's feet down into some cthonic oblivion where it belongs, possibly as the natural food of well-intentioned supernatural toads under the earth. That’s just a theory though.

drove with the windows rolled down while lugubrious enka music poured out of the radio. A touch of home feeling to that cab.

Hot springs ryokans are smaller and much more personal than hotels, with breakfasts and dinners planned for you, and hosts who assume you will want to take as many baths as possible in the time allotted. We were greeted by name as soon as they saw us. I guess we were easy to spot as Westerners. The outside of the ryokan was not ostentatious but the interior was astonishing; the building was constructed around a garden separated from the lobby, the tea room/bar, and the corridors by glass walls. The garden was a masterpiece of little pools, miniature black pine, miniature bamboo stands, tiny maples, and gorgeously weathered rocks delightfully carpeted with a careful selection of the finest mosses. It was quite impossible to tell from any one angle how large the garden was (it turned out to wrap around the two wings of the ryokan so each room had its own private garden view, no two alike).

Nikko is deservedly famous. In its heyday, not so long ago, Nikko was of considerable imperial importance. The Taisho Emperor had his summer home, the Tamozawa Imperial Villa, at the foot of the hill our ryokan was on;

indeed the ryokan seemed to have been somewhat influenced by the villa.

considerable refurbishment. It is now a museum. We learned all this by stumbling over it. I had no idea such a thing existed or that I would soon find myself standing in the Taisho Emperor’s summer throne room. Truly we are surrounded by little miracles.

The Tamozawa Villa seemed not only comfortable, but somehow familiar. Probably it was the plants. We saw Nikko hydrangeas, Nikko spireas, and all sorts of other plants that Karen and I have grown for years, in our current garden and in the garden before that. As Alex said, we apparently traveled halfway around the world to look at the bushes in my own yard. This was to become a refrain of our trip as one nostalgically familiar plant after another presented itself on roadsides, outside train windows, in gutters and in gardens. It turns out that plants are a kind of universal language after all.

The day was turning cool and wet. We bought an umbrella to protect us from the rain misting down from the low clouds. A shop lady came out onto the sidewalk and literally herded us into her combination general store/dinette. Thus we discovered the breaded pork cutlet with curry and rice. It was fresh, handmade and truly delicious. Japanese curry is not really curry; it is a mild curry-flavored gravy. If you have it in the train station it might not be spectacular—it’s necessary to find a diner where they’re making it out of real pork chops and stewing their own curry gravy. This dish would have been utterly alien to the Tokugawa shoguns whose funerary monuments and associated shrines litter the surrounding hillsides.

In English-language travel literature, the Tokugawa monuments are often described as too florid to be in the very best architectural taste. It might help to view them in reverse order with no idea which one is which, as we did. Ignorance sometimes enhances appreciation.

old hands in no time.

Move It, Gramps

The last of the grand shrines we managed to get to was the Nikkō Tōshō-gū, built by the Third Shogun, Tokugawa Iemitsu, for his grandfather Ieyasu, founder of the dynasty. It is a multi-tiered complex of structures whose summit is a long series of stairs and ramps leading to the Shrine of the Sleeping Cat. In the walked-out confusion of a long day, I wondered if the Shrine of the Sleeping Cat was actually the shrine of a cat or perhaps for the veneration of cats generally. After we made the daunting ascent to the Shrine of the Sleeping Cat I remember remarking to Alex that our late cats, Tiberius and Calpurnia, deserved a shrine like this and if I ever hit the lottery all our cats would have their remains moved and get a nice shrine.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tokugawa_Ieyasu

That shrine was closing for the day and the priests were requesting that people leave. A pleasant young man with a wife and small children replied, “I’ll do what you say—I don’t want to be sent to hell.” This was the first complex Japanese sentence I managed to understand in the wild, so to speak. While hardly sesquipedalian, just for an

instant I felt linguistically adroit. I owe it all to Jigoku Shojo.

As the sweating mob of visitors poured down the last flight of stairs to the main shrine, another priest said “Move it, gramps,” (“Ikimasho, ojisan”). When I looked around to see who this officious young whippersnapper was addressing, I realized it was me.

Ghosts

buildings, of which 15 remain.

guests in the shuttle bus seemed delighted to have us climb in next to them, huge soggy westerners sweated through from a day of crawling around the mountainsides in mist and rain.

Day of a Thousand Konichiwas

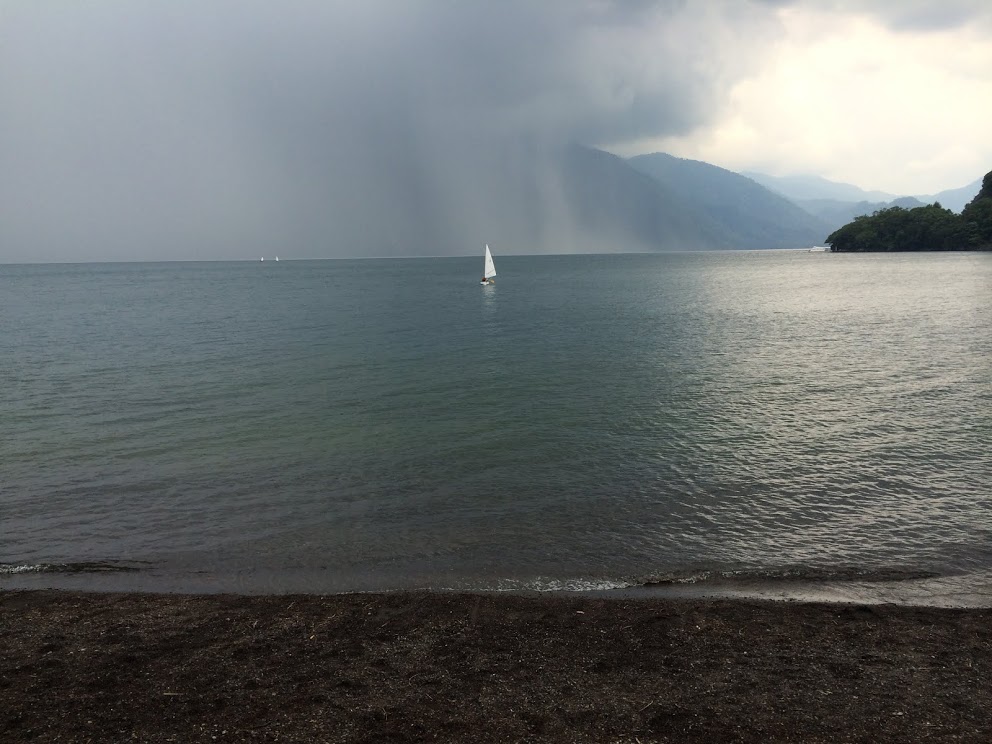

forest, whose acute weathered slopes are volcanic in origin. Mount Nantai above Nikko is the genius loci of this landscape. The huge lake was impounded by an eruption about 20,000 years ago, and the moors and bogs in the uplands might well be decaying lava terraces.

no, wild animals!" In English!

for a while and decided that we were nowhere near walked out. We were game for miles to come. Another bus stop was available just three Japanese kilometers along the lake shore. We decided to walk along the lake.

fully wet there’s no way to get wetter.

We found a deer skull on a stair railing. "Do you think it's a warning?" Alex said. "I think it drowned in its tracks."

and tales of its origin vary, from the distance a hypothetical peasant can run in an hour carrying his own weight in firewood to the exact distance no one would want to walk in a downpour.

It stopped raining when we reached the bus station. The rain had disrupted the bus schedule back up the mountain, where the roads were mostly hairpin plummets. Ultimately a considerable gaggle of damp people gathered, waiting to be packed onto a replacement bus as soon as one could be found. It took a long time to get back to Nikko.

I'm sure Alex and I looked a muddy, bedraggled, gasping sight as we staggered back into the precincts of one of the most gracious and elegant ryokans for miles around.

They Said They Were Americans But They Were Really Tanuki

Everyone at this wonderful place was invariably well dressed (except in the bath, where the sexes were segregated and clothing was not an option), cool, calm and collected, poised, beautifully mannered, plainly relaxed and enjoying themselves tremendously. It was a place for distinguished people of taste and income to meditate over their tea after a hot springs bathing experience, while gazing upon a masterpiece of Zen gardening in surroundings dignified by an astonishing history of power and prestige. Westerners were unusual here. We got to wondering if were the tanuki in this lovely place -- a raccoon-like animal, in ancient times believed to have magical powers, who sometimes masquerade as humans for fun and mischief.

“We fit in perfectly,” I said. “We stave off hermeneutic stagnation, provide variety and amusement. Our role is to be different and slightly crazy.”

“They said they were Americans but they were really just tanuki" Alex replied.

“After they checked out, all the money they spent turned back

into oak leaves.”

RSS Feed

RSS Feed