There are some mysteries. Where ancient towns of note already stood, stretches of preexisting superior local road must have existed, suitable for incorporation into the main Roman road. This seemed at first to explain why the Via Flaminia climbed the considerable hill of San Gemini. But upon closer examination, at San Gemini the Via Flaminia apparently bypassed a considerable Umbrian hill town and religious complex at Cesi, from which a fairly direct older road ran north—joining the Via Flaminia at Carsulae in fact. Meanwhile, as best I could learn, San Gemini in Roman times was a post stop on the road, not a major town.

The modern roadway from San Gemini to Carsulae—not too modern—scrambles cross-country from one farm to the next more or less along the old Via Flaminia route until it reaches a switchback a few hundred yards due south of Carsulae. There a modern farm sits athwart the ancient road. On Google Maps the route of the Via Flaminia into Carsulae is clearly visible from the air paralleling SP 22.

Map data: Google, DigitalGlobe.

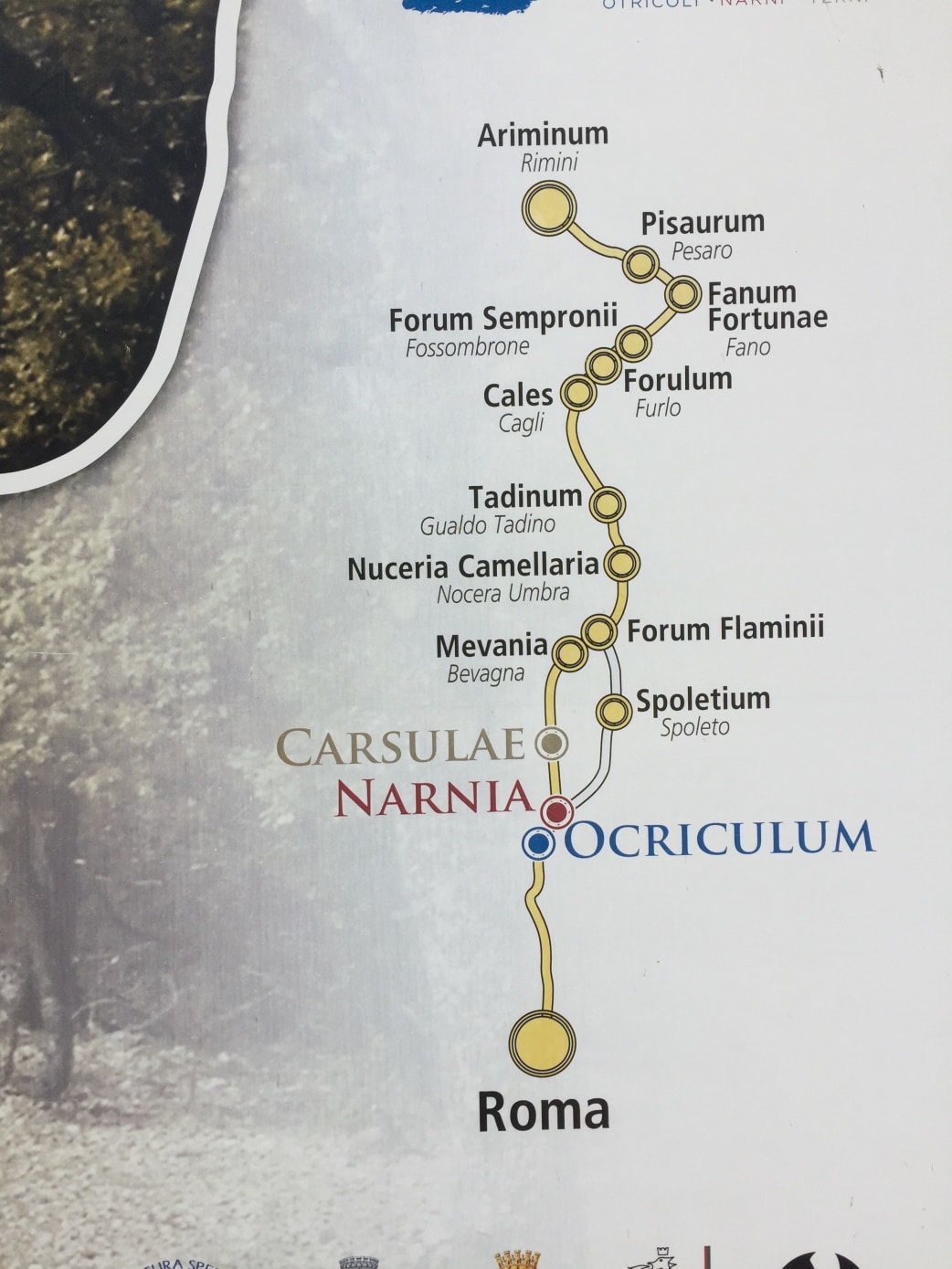

C.S. Lewis borrowed the name for the fictional kingdom ruled by Aslan the lion in his famous Narnia series.

Early postclassical Narnia on its steep and massively fortified hilltops was not a place that Goths or others could simply charge up and seize. It was not vulnerable. Today, considerable Roman and medieval points of interest coexist peacefully in a living town, one of the larger if not the largest of the Umbrian hilltop towns. And once again the Via Flaminia is seen to climb a considerable small mountain, the best explanation being a well-engineered preexisting road convenient to the accommodations in a thriving city.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed