When Germany invaded Belgium in 1914, Great Britain sent its small but dedicated professional army, the “Old Contemptibles,” into Belgium. While getting into positions around the town of Mons, the British discovered for the first time the incredible size of the Kaiser’s military juggernaut. The first reports from British airmen scouting the German advance were wrongly dismissed as hallucinations, but in reality the British in Belgium were massively outnumbered at all points, leading to the headlong running engagement known as the Retreat from Mons. Characteristically for the Great War, the Retreat from Mons was regarded as something of a victory by both sides. However, it was thought politically and militarily unacceptable to give up all of Belgium to the Germans. British strategy demanded that some part of Belgium be held. Ieper, a road intersection covering the Dunkirk-Calais coastline, seemed a fairly obvious spot. Though the town itself is low-lying and sits in a sort of bowl surrounded by shallow ridges on three sides, the ridges themselves were selected as good defensive positions.

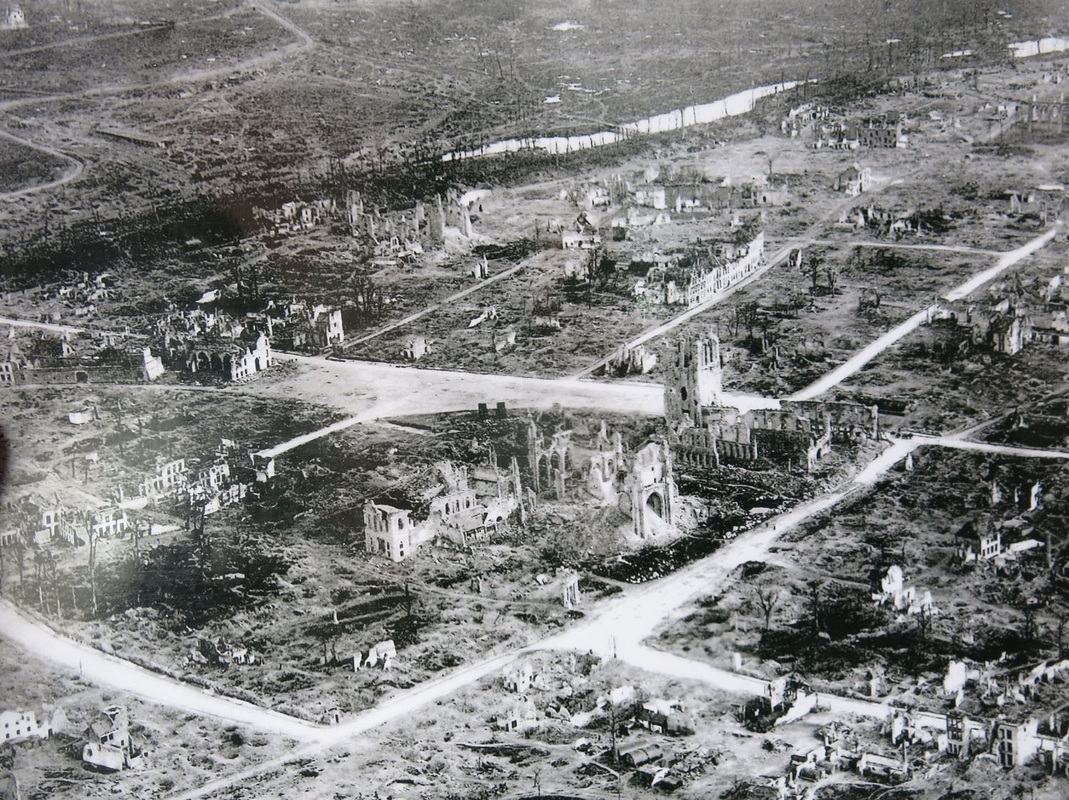

The Kaiser’s army attacked ceaselessly to drive the British and Commonwealth forces out of Ieper. Attacks and counterattacks continued nonstop for the rest of the war. Poison gas was used there for the first time in history, with some success, and the British lost the ridges and found themselves confined to the lower areas of the Wipers Salient, surrounded by German artillery on three sides. The water table was so close to the surface that most trench lines in the salient had to be built above ground out of sandbag parapets. As the agricultural drainage system was destroyed by shellfire, the salient turned into a bottomless morass and countless men simply drowned in the mud.

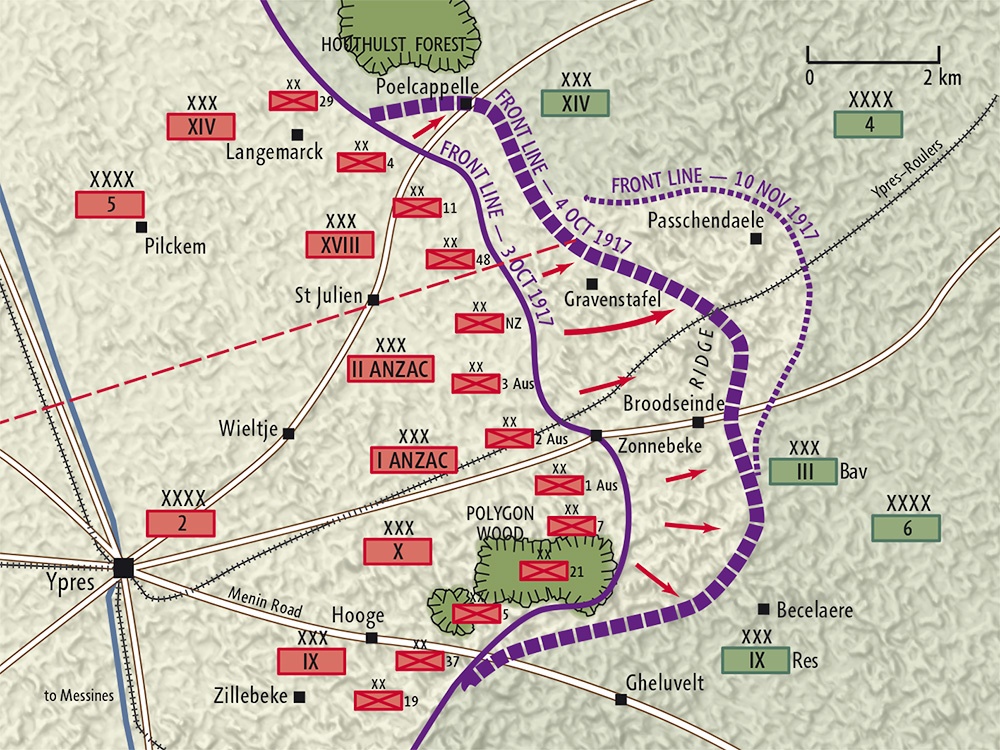

In one offensive after another, British and Allied troops fought their way back up out of the salient, culminating in the horror known as the Passchendaele Offensive of 1917, where with almost unimaginable losses to both sides the British finally regained the ridgetop they had been unable to defend in 1914—only to lose this ground again in the final German offensive the next year. The map below shows the final British offensive.

In our GPS-monitored writhing from one rural traffic circle to the next, we effectively lost track of where we might be in relation to the town of Ieper itself until we reached Passchendaele and the monument to the high water mark of the British offensive of 1917. We were in the Salient, arriving by way of the ridge the English soldiers called Passion Dale.

In 1917 people died by the tens of thousands to get to Passchendaele, and ironically the survivors who lived to see the place would rather have been somewhere else. The fields sloped off extremely gently as we drove on to Zonnebeke, where we stopped for some delicious beer and then toured the excellent new Memorial Museum Passchendaele 1917 (web link below).

http://www.greatwar.co.uk/ypres-salient/museum-passchendaele-1917.htm

Our schedule did not permit much museum-visiting but without something of the kind we had no chance of really getting oriented in the Wipers Salient. The Memorial Museum Passchendaele 1917 makes a great introduction to the trenches of the Great War, not least because of its meticulous reconstruction and/or relocation of original bunkers, both deep and shallow ones, along with an idealized reconstructed trench. Among its fascinating displays were tactile exhibits where one could handle some of the typical equipment of soldiers, and in the gas exhibit we were allowed to enjoy a tentative sniff of each of the varieties of poison gas used in the Great War. They all turned out to smell pretty foul, like various forms of bug spray.

Photo by Gary Mawyer.

Photo by Gary Mawyer

Photo by Gary Mawyer.

Polygon Wood provided our first trench walk and cemetery. Many of the Australians, Canadians, British, Germans and others who fought there remain nearby to this day. We saw about twenty visitors, mostly Australians and British; we may have been the only Yanks present.

Photo by Gary Mawyer

Photo by Gary Mawyer

(Wikipedia)

Photo by Gary Mawyer

Photo by Gary Mawyer

Today when one drives across the Salient it doesn’t seem very far. One could walk it from end to end in a day, with plenty of time left over for lengthy beer stops. Wipers has a great literature, and in that literature Wipers expands to the size of a small planet, a world of its own whose landmarks loom with fatal significance. Movement within the Salient was phenomenally hard in the Great War. The ground was fractalized into webs of barely passable trenches. Rains of shrapnel, high explosives and poison gas were frequent. If you were lucky the mud was only knee deep. And the last fatal thing many soldiers did was climb high enough to see where they were going. Thus sites within the salient acquired and still have legendary auras of unreachability, almost mythic significance, crowned of course by Passchendaele Ridge. A week could be well spent in Ieper and probably three days ought to be considered the minimum for a comprehensive tour. Our day and night was necessarily a brief cross section.

As the sun went down and the tourists mostly left—Ieper being quite a small place—the meticulously rebuilt streets emptied and a Flemish School afterglow set in.

Photo by Gary Mawyer

Photo by Gary Mawyer

Photo by Gary Mawyer

Photo by Gary Mawyer

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Island_of_Ireland_Peace_Park

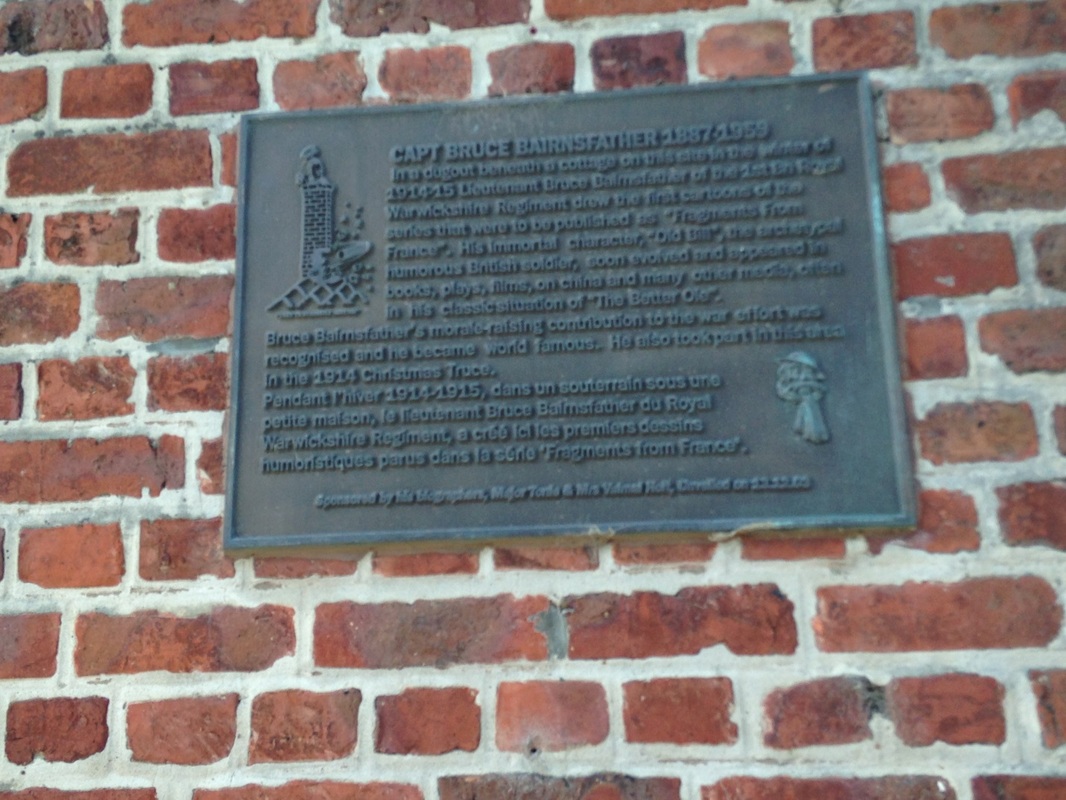

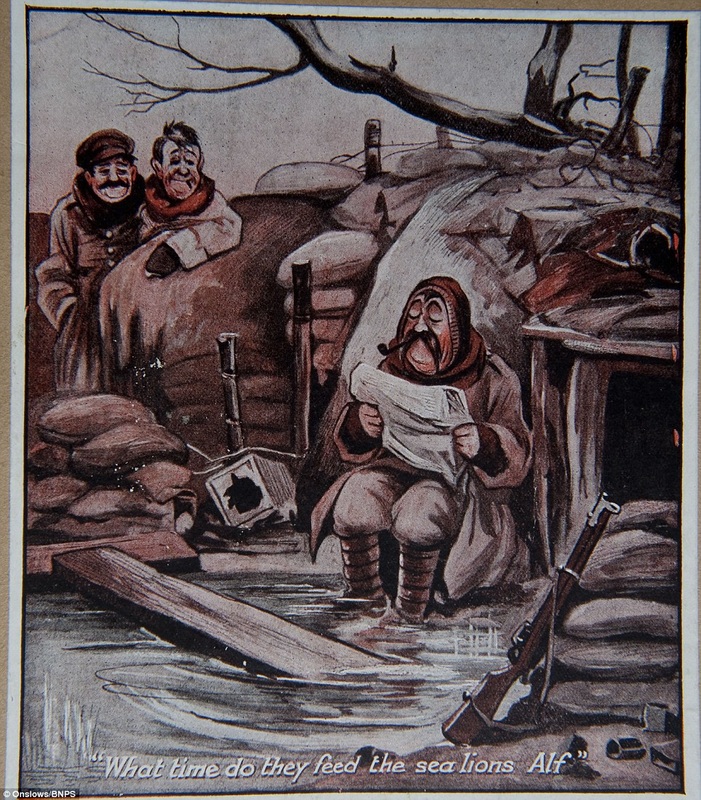

At Plugstreet we found the Bruce Bairnsfather Memorial, a plaque commemorating the satirical cartoonist who made the Wipers Salient funny and provided the immortal Fragments from France series. Though wounded at the Second Battle of Ypres, Bairnsfather survived that war and cartooned his way through the next one as well.

Photo by Gary Mawyer

Photo by Gary Mawyer

Photo by Gary Mawyer

Photo by Gary Mawyer

Wipers is a perfectly rational pilgrimage spot for Great War battlefield historians and for students of early 20th century British literature, as well as for countless descendants and relatives of the people who fought there. During our visit, Australians were very much in evidence. We gathered from our conversations that American visitors are scarce. As Mark Twain said, “God created war so that Americans would learn geography,” but in this case it may not have worked. Wipers does not really fit the American psychology. We Yanks like the particular, and especially the sentimental particular. At Wipers, well over 100,000 soldiers of all sides still remain missing, and a few hundred thousand more died, on the shelving wheat fields around one Belgian village. The American world view does not have a category for facts so complex and unsentimental. We like it when justice is seen to be done and Lassie comes home, and Wipers seems to be saying that maybe the world is not really like that.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed