Over the Top is a bloodthirsty and horror-raddled story with episodes that might have nonplussed Edgar Allen Poe — a phenomenal tale of unbridled violence and terror mixed with equal parts sadism and schadenfreude. This is an adventurer’s first-person account rendered with plain, unselfconscious simplicity. Empey’s comical bayoneting incidents and accounts of casual dismemberment, not to mention his apparent enthusiasm for trying to shoot people through the head, suggest a solipsist with a strongly inhibited sense of empathy.

As a 10-year-old reader, Over the Top amazed me. I remember wondering if this story could even be true. Of course I knew about World War II; 10-year-olds of my generation already knew a lot about World War II. We played soldiers with our war toys incessantly. I even had a treasured stash of patches, insignia and badges from Normandy and a whole fruit salad of European campaign ribbons, items I rescued from the trash when my grandparents’ next-door-neighbor threw them away. Every kid on the block had a reasonably good supply of ammo belts, clip pouches, canteens, mess kits and other field gear left over from World War II. We had lots of context for World War II, including incessant war movies, but no context for the Great War. Adults never spoke of it. It wasn’t a famous event.

At first Over the Top might as well have been science fiction to me. That changed quickly. I had to know. A few trips to the library later, I could be sure it was all literally true. Empey may not have had the imagination to invent any of it. Lack of empathy, acute self-obsession, default of imagination; perhaps the author of Over the Top was a very good candidate sociopath, in the end. But that is an adult thought.

Over the Top seemed to me a strange echo of a very distant and forgotten time. In fact, it had only been 43 years. Arthur Guy Empey was still alive when I stumbled over his book. By comparison, it would be like a kid in 2014 reading about the fall of Saigon. That’s the thing about history. It’s always closer than you think, like the skeleton hand on your shoulder in the fun house.

Karen reminded me that we did not have much library access in those years. That’s true. We had a once-a-week school library period lasting one hour, but circa-1960 school libraries in Charlottesville seemed

deficient even then and would horrify us now. The University of Virginia had one of the best research libraries in North America but as school children we had no access to it. The public library, located at that time in the handsome McIntire building that is now the home of the Albemarle Charlottesville Historical Society, was unusually good for a town this size, but its children’s section on the lower level was very humble. Some badgering was required for an adult card at age 10, and to use the city library I had to walk two miles each way. The bus cost a dime and my weekly allowance was a nickel. I enjoyed the walk.

the 1906 edition.

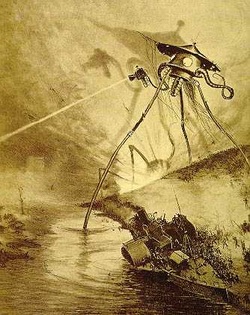

imaginative powers, and lack of empathy -- qualities the old monarchical empires of Europe required in order to function in the world they had so thoroughly colonized. Of course no humans expressed these qualities better than the hapless Martians, with the possible exception of the Czar, the Emperor Franz Josef, and poor old Kaiser Bill. Or Empey. Or maybe war lovers in general. Hmmm.

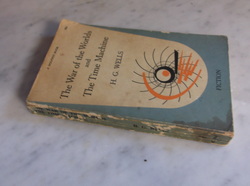

At age 10, reading the War of the Worlds gave me the context for the Great War -- a world was ending. The Battle of France was no irrational outburst from an unintelligible stream of events matching MarkTwain’s definition of history as “One damned thing after another.” The Great War was structural, to the point it could be predicted, and was predicted -- just not by enough people, or by the right people, to be avoided.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed