http://quoteinvestigator.com/2015/10/25/comma/

I stayed up most of the night quite frequently for several decades, and I was busy writing, but that was as much coincidence as cause and effect. For a score or more of years, I only wrote when I couldn't stir up a card game or a board game.

Three or four descriptive paragraphs or a dialogue string seems to me to be a sitting’s worth of work. This gets you within sight of 365 pages a year if actually held to. And yet this is a trivial amount, the size of an email, just an effusion. Ten paragraphs a sitting can be heavy work, but the serious dilettante should reach that pace now and then. And that pace is enough. Writing the words down, or inscription itself, is not the most important part of the craft or practice of writing. If an expression or supposed expression resists itself or seems to need an application of force to put down, then the expression is being assembled wrong and the units need to be looked at again.

Design and material are inseparable. Material defines the range of possible designs, and the purpose of the design is to master and represent the material. If equipoise between material and design is achieved or approached, the execution cannot help being “good.” This is obvious enough in pottery or glassblowing or painting.

The weird, webby quality of language, grammar and words generally helps us forget that writing is also a tactile art. Drawing is a tactile art, and sketching, and calligraphy. Handwriting is not usually called an art but from its first stirrings clutching cigar-sized First Grade pencils, it’s self-evidently a tactile expression. Even when subordinated to the idea, and to the thralls of language and grammar, and in the modern era where the electronic keyboard is king, writing is still a tactile expression. It’s not just a form of reading, or the reverse of the reading process. Writing is an inscriptive act. Its link to ideation is not exact.

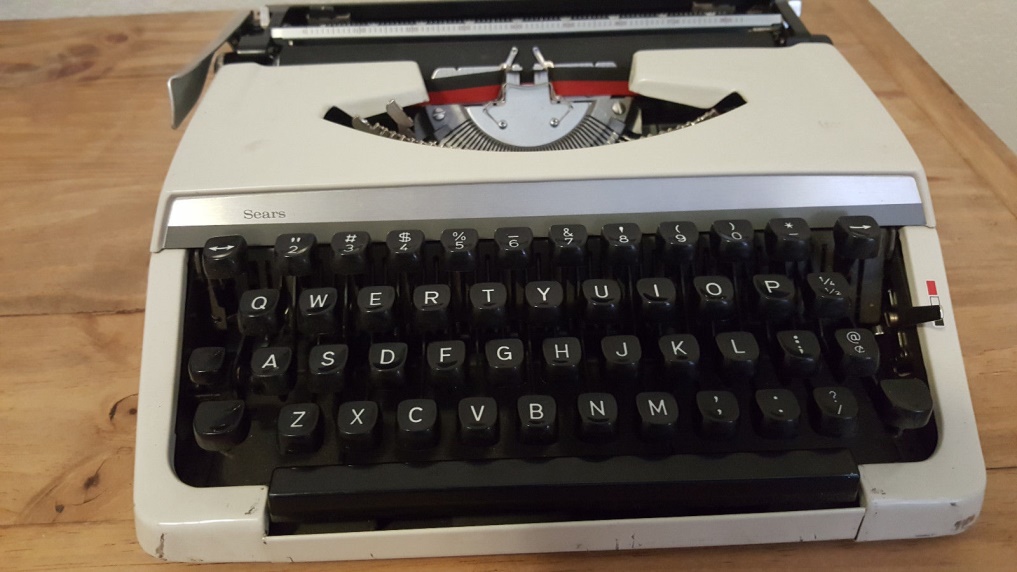

Sometime in the early 1960s my mother Hazel decided to go back to work, and invested in a Sears portable typewriter and a typing manual to brush up on her pre-marriage typing skills. My brother Alan and I were still in elementary school, I think. When Hazel went back to work I co-opted the Sears typewriter (but not the manual) and fooled around with it for the next few years typing various things. I didn’t use it for homework—I didn’t want to panic my teachers. I mainly enjoyed playing with this small, comprehensible machine, and working the machinery. Soon I began to get to a decent 5-finger typist stage. However, the 1960 Sears portable was a very basic machine with a beige-colored shield, stiff keys and a very flat click. It was a sad enough little device. The one in the picture here might as well be the same machine.

You would think that would never happen. Why would kids puke? But the truth, as the years have confirmed, is that kids puke more than you’d think. I found myself mopping up puke in Standard’s Drug. I’m still a little resentful about it fifty years later. But I had a motive.

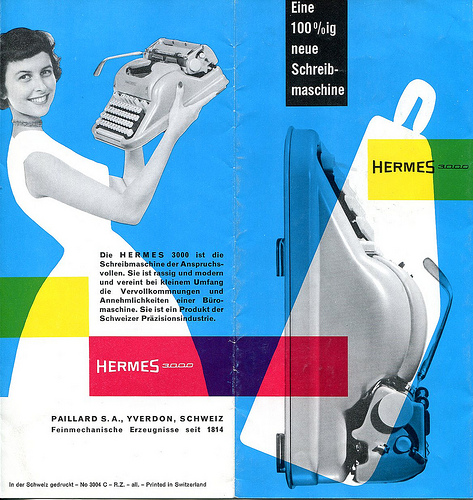

So I grudgingly counted down from paycheck #1 to paycheck #5, at which point I quit on the spot, turned in my mop bucket, and bought the Hermes in the window on the way home. I carried it home on foot. We seldom felt like spending a nickel on a bus ride. Indeed we walked everywhere we went; if we were in a hurry or needed to get completely across town, we just walked down the railroad tracks instead of the sidewalks.

“The Centre For Computing History” - http://www.computinghistory.org.uk/, CC BY 1.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=32890425

Since then I have just typed on throw-away keyboards, which have much sameness. And yet even on keyboards and mice, inscription remains manual and is still a tactile act.

I feel I have a firm tactile grasp of what comes up from the keyboard when I practice writing, but little way of typing an explanation of it. It’s certainly not my intention to tell people things. I leave that to others. The bits of writtenness on my screen are artifacts of a given moment. The paragraphs or larger units are a sort of ornament. They are “a thing to look at.”

Such pieces of writing, or word accretions, are not viewed in a vacuum. They are viewed in the material world, possibly by people who are only reading something at that moment because they are sick in bed with the flu and feel terrible.

Or, for a happier image in the Christmas season, paragraphs are like the decorations one hangs on a tree or wreath of thought. The tree or wreath must be there and be fairly stable. Then the artiste can open his bins and baskets of ornaments and strands and work them all over the tree for the desired effect. The result is inevitably a Christmas tree, but hopefully readers trust that the undecorated space behind the words is not empty.

My personal mnemonic is not a palace--not even a cottage; styling it a Memory Tree may even be too grandiose. I think I will call it a Memory Weed Lot, where opportunistic memories twine through each other toward the light, growing, dying and seeding season by season.

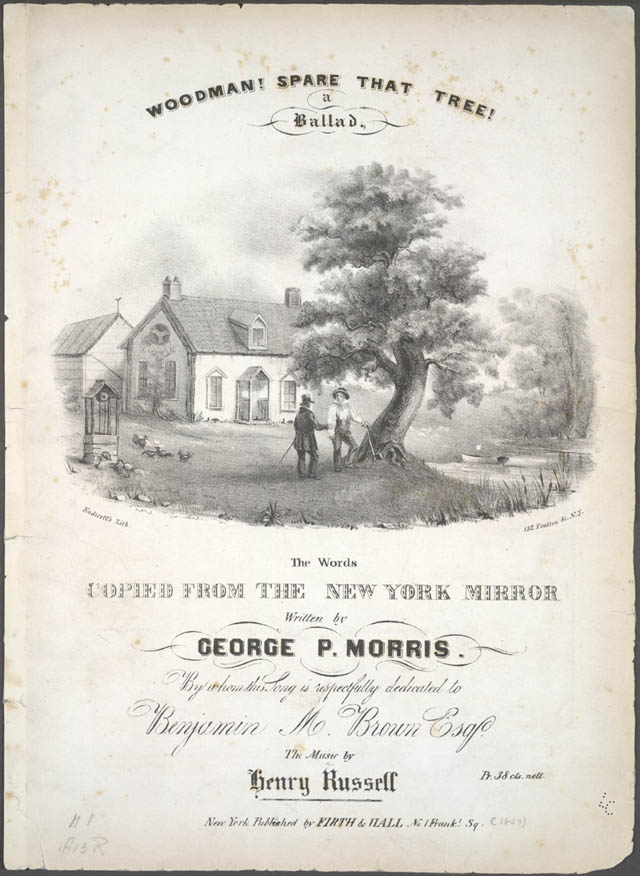

WOODMAN, spare that tree!

Touch not a single bough!

In youth it sheltered me,

And I’ll protect it now.

’T was my forefather’s hand

That placed it near his cot;

There, woodman, let it stand,

Thy axe shall harm it not.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed