The thrifty reader (is there any other kind?), not to mention the critic, might ask if the Complete Adventures merely collects the previously published serial stories and the first small collection. No. The core is entirely new. The previous stories, now in chronological order, have been rewritten around the core, and the result is not a story collection but a novel, despite the misleading Adventures of the title.

|

This post is more announcement than blog: The Complete Adventures of Rhesus A. Macaque, Private Investigator, is available on Amazon in Kindle and paperback. Started some time before 2009 as a short story with my co-author Edward Mawyer, Macaque grew; it became more and more serious and also funnier and funnier. It evolved into science fiction, then prophecy. The earliest versions were steeped in the fin de siecle mood with which our century began. The Complete Adventures, fifteen years later, are optimistic instead; and, I sincerely hope, uplifting. The past of those days is gone. We need look for it no more. Even our historians seek it in vain. Instead we have a new past rising rapidly before us, something we will have enjoyed very much at times, replacing all that came before.

The thrifty reader (is there any other kind?), not to mention the critic, might ask if the Complete Adventures merely collects the previously published serial stories and the first small collection. No. The core is entirely new. The previous stories, now in chronological order, have been rewritten around the core, and the result is not a story collection but a novel, despite the misleading Adventures of the title.

0 Comments

I’ve come to feel almost familiar with Oahu. I know the map. Honolulu is stuck in the nexus of several high valleys that don’t connect at the top, and this city shaped like an octopus has octopus roads and highways, but the expressway will let you out easily enough except during the long rush hours. But my feelings of familiarity are illusions. Maybe I finally know Hawaii just well enough to realize how little I know. I agree with Violet Paget; you can only know a landscape by walking it. Paget distinguished between the automobile (of her day, possibly steam-powered), the carriage, the railway train, horseback, and on foot. We can now add the airplane and the satellite, and all these ways of knowing provide their own independent information, but in the end we are animals. To know a place on the level of the animal, the animal has to walk it. Oahu beach. I have not walked enough of Hawaii to know it. On foot, Hawaii is the size of kingdoms—fairy-tale-sized kingdoms with what to a landlubber falsely appear to be obvious borders, the channels between the islands. Of course the channels connect the islands, and the sea is the largest part of Hawaii. Hawaii’s borders are far beyond the horizon. So mainlanders don't get Hawaii--we see it backward. Thus we have the idiom “mysterious island” in our westernized/westernizing world culture, from the Odyssey to Jules Verne and old 50s movies, ready to furnish man-eating plants and have a secret. It doesn’t matter what the secret is; we merely have to not know it—to keep the secret, even from ourselves. Such is the outsider’s knowledge. Secret Oahu. It's a place of friends, relatives, and good memories. Are friends electric? My fellow editor and poet extraordinary, Pat Matsueda, and self in the Honolulu night. This fall was my first trip to Maui. Maui is far larger than it seems by car, due to the road configuration. Maui’s larger than Oahu but the driver on Maui inevitably crosses and recrosses the old sugar cane flats between the two volcanoes and this sense of X stands in the way of appreciating the island's real size. Sometimes I think maybe nothing is entirely wrong, even our fairy-tales. The islands of Hawaii were once warring kingdoms, and on Maui as on the Big Island the ruins of fortifications can still be seen. Hawaii’s warring states era was conducive to ruin, we can be sure, and mercifully the wars were ended by Kamehameha with the unification of the islands into a single polity. Kamehameha's cannon at Lahaina. From Kapalua on Maui, the island of Molokai looms to the north. Plumeria. A thousand uses, such as playing with your food. For Kamehamea, and for the Pacific whalers and traders and eventually for the U.S. Navy, the Lahaina Roadstead on Maui was a strategic locus, the navigational key to the whole Hawaiian chain. The Kingdom of Hawaii, founded on peace and aloha, had no defense against the barbarians from the sea, heavily armed, bringing rum, disease, missionary disenablers, and the attempted destruction of a complete civilization. The Lahaina Roadstead. Relics of the whaling fleet at the jail in Lahaina. On the Lahaina waterfront today. Maui is a place of enormous historic significance and depth of identity. The reticulation of identity, kanaka maoli, haole, local, tourist, customer, owner, homeless guy in culvert (can also be any of the above), persists on the sidewalk in Maui’s interesting and relaxed hippie towns. Somehow the god of the volcano seems to have an eye on everything, Maui himself. They say the huge stone bones of Haleakala are dead. Tourists off the cruiser might not even have the time ashore to realize how careful Maui is, everybody walking around calm but strangely alert to the god over their shoulder. Wailuku. On the road to the volcano, proteas were for sale from protea farms on the roadside. Proteas are a rare survival from the Cretaceous Period, a vastly ancient flowering plant native to South Africa and to certain other land masses that were originally part of Gondwanaland. Hawaii seems a perfect habitat for protea, but they require a master gardener. My daughter-in-law Kahiki and Proteas. Hard to believe these are real but they are. The long winding road to the summit of Haleakala passes by a curious arts & crafts era legacy, Hosmer Grove. The Hosmer Grove forest preserve was started by Hawaii's first territorial forester. Quoting Wikipedia, “Ralph Hosmer imported tree species from around the world in hopes of creating a viable timber industry. In 1927 he began planting stands of pine, spruce, cedar and eucalyptus at this site, which can still be seen today in the grove. Only 20 of the 86 species introduced survived.” Hosmer's Grove eucalyptus. Where the honeycreepers lurk. Eucalyptus and pines are doing well, but not the white pine and the eastern red cedar, two trees native to my yard in Virginia, which never had a prayer on Maui. This densely tangled temperate forest is well known to bird watchers as a top spot to see honeycreepers. We saw five male i’iwi and they are the miracle mentioned in the title of this blog. No prayer of getting a photo of a bird in my case, since they fly like rockets, but the antique lithograph turns out to be pretty accurate. The scarlet i'iwi. There is something special about volcanoes. It’s partly their creative nature. The volcanoes of Hawaii have a solid history of creating big things—Mauna Loa, Mauna Kea, Kilauea, and on Maui the sleeping Haleakala, and an epic hiking trail system, the Sliding Sands Trail. The summit of the trail system, over 10,000 feet above sea level, is astonishing. We walked as much of it as we could under the circumstances. Volcano trail in the clouds. The big volcanoes remind us what’s under the surface and how our planet works. When the volcanoes stop, our planet will be as dead as Mars--spent. Glimpse of the opposite rim. Farther than it looks, much much farther, on Haleakala. Ten thousand feet. The flightless Nene, wondering why everybody feels like they have to mention that. My son Danny lavishing it up on the sands. Mysterious island--last shot on the roll.

The indispensable garden writer Elizabeth Lawrence pointed out, justifiably, that summer gardening is impossible in the south. I paraphrase, but she essentially averred that spring and fall were the gardening seasons and if a plant could not live past June without being tended, it had best die. I agree completely, though it’s possible to have a fine high summer garden using plants that only need to be tended in the spring and fall. The big lilies--trumpets, orientals, orienpets, and many species lilies—stand out for carefree summer growing, along with such things as gladiolus, phlox and any number of hybridized field flowers. A portfolio of lilies. Of course that doesn’t speak to weeding, especially in a wet summer like this one. Intense thundery heat sends weeds skyrocketing. Dense weed patches spring up in days. Twilight and earliest morning are usually bearable for garden work if the thunder hasn’t set in yet. Other times, it's hard to work in the open. That's why gardeners don’t usually get to see their own gardens. Gardeners tend to see what they are trying to do—imaginary things no one will ever see—or they most easily notice the things they are failing at—rather than what, if anything, they have succeeded at. The garden tools themselves command most of the attention. Otherwise they turn on you. Like our old Holocene monkey-folk ancestors used to say, “When you pick up a tool, you’re shaking hands with danger.” The cicada—arguably the god of summer. We’re being prickled, stung, bit, clawed and prodded anyway, scampered over by innumerable weird insects large and small, smeared with mud and mulch and fungi, protozoans and bacteria, not to mention plant saps and pollen. Imagine it without the tools—impossible. You bleed, and how the other life forms enjoy that! Watering a garden with your sweat is no mere metaphor, but if you want every living thing in the garden to truly exult, try bleeding all over it. Turns out everything loves blood. Even the nectar feeders think it’s pretty funny. Hover fly on Phlox paniculata—one of the most highly evolved fliers—a nectar-feeder whose flight and appearance mimic the hummingbird and the hornet. I love lifestyle articles on garden tools. So many of the best tools are Japanese. The gardener needs the braces, however, even more than the tools. Without the braces we cannot use the tools. I refer to the inevitable back brace (I recommend the Mueller), the equally fundamental knee brace, the vitally necessary arm brace, the thumb brace, the garden variety wrist brace, the common Desert Storm army boot (because a thin covering and a little bit of sole will not shield your feet from insult or provide the desperate margin of grip to keep us from plunging onto the spikes below). And the hat, by god. Hat or die. You want the neck flap, the wide brim, the absorbency. The clever straw hat is only for style. The Japanese Infantry or Foreign Legion style adds a lot more wicking surface to help ‘cool’ the back of your neck, if that’s the word we’re looking for. Meanwhile there’s no telling who or what shares the garden with us. We haven’t got time for that sort of thing. A tortoise. Treena, the garden’s owner. Karen in the garden. Karen also owns the garden. The vegetable garden is hers, and there is no abandoning the vegetable garden just because it’s 101 F and 99% humidity. These are the plants, some ancient and some more recent, modified by humans to produce food. They live and die in infantile helplessness, some more so than others. Too many diseases. Too many predators. Our big fat invading groundhog, Cyrus the Great. The beetles. Meet the beetles. The art of growing vegetables is fundamental to being human. In its infinite calculation and near-impossibility, food gardening is one of the most complex acts the old monkey folk ever took up. We know they did well enough to produce us. At least as well as that. Can we do better? Please try! Summer changes things. The main wheelbarrow route taken over by a pumpkin vine. The foot of the vegetable garden is to the right. There’s many valid perils in gardening that deflect our vision away from the stunning displays flower beds afford. As Thomas Gray said in An Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard, “Full many a flower is born to blush unseen, And waste its sweetness on the desert air.” Then summer ends and with fall comes the inevitable next book. As of yesterday, Shad River is freshly available on Amazon Kindle. History—where does it come from? What is history anyway, but the stories of peoples’ lives? People begin as members of families, then as members of communities. Families and communities are the raw sources of history. In Shad River, place is the protagonist. Individuals and families come and go while time melts and reforges a river-crossing community that began before history in the Virginia mountains and has had many faces since. Shad River is a picture of that history’s American moment. A tiny handful of people around the world have run across Rockfish, my old terribly long experimental historical novel. The Rockfish enterprise entangled itself with decades of my life, which was never my intention, but it made a useful proving ground. Saying goodbye to this OOP oddity required writing Shad River instead. Shad River is retrospective writing--naturally, as a historical novel, but also structurally as a look back on a former book. It will take a couple of weeks to produce a paperback version for those like me who prefer a hard copy, but that is coming soon. Meanwhile Shad River is done, and summer is done, and I can return to my macaques and roses, because fall is when the real garden work gets done. How to use catnip. So much work. Awaiting a tile job... my fall task. Sometimes you grow an exotic curiosity just for thrills.

Don and I drove across quite a bit of the high plains, and spent days canvassing the back wrinkles of the Rockies. It was time to get back to real life, and Yellowstone National Park was the most natural contact point. West Yellowstone was mobbed with people from all over, and I was soon running around with my wallet in my hand like everybody else. Tourists so far were comparatively few on this trip, except for the spectacular Museum of the Rockies. When we entered the park, in a plague year, and with the sky dulled by the flames of California, we wondered how many people we ought to expect to see. But 2021 was apparently the year everybody went to Yellowstone, breaking all records for visitation. Sick and tired of public disease and desperate to get away from privacy. We asked: do we imagine the park as a reservoir of wildness surrounded by property and development? Or imagine it as the exposed tip of a greater wildness beyond and outside the park? Is that right? What do I think? I think it’s a great thing to be here at all. Yellowstone is the massive caldera of an incredible supervolcano and a relic of the formation of the Rockies, leaving a trail of previous calderas behind it all the way to Utah. The caldera answers a lot of questions, such as the geologic-sized Idaho ashfall that provided much of the physical material the upper Great Plains are made of. The instability of the earth seems somehow akin to what we call art. Ragnarok's Thumbprint—one of the many geyser fields in the caldera. Phantasmagoria in the forest. The Soap Pit. Traversing the Paint Pots. The ghostly blue of the sapphire geyser pools seems like an exhalation from some other dimension—but it’s our dimension. Yellowstone is well over 6,000 feet above current sea level. It is entered through mountain passes. Lewis and Clark did not find it, which seems strangely un-iconic of them in this part of the world. In the end I don’t know exactly what to say about Yellowstone. It’s a civilizational monument. It would still be there without the NPS, but in what form? Northern rim of the Yellowstone Caldera on the way to Gardiner, Montana. Thinking back to the beginning of our trip, with reference to Roadside Geology of Montana (why set foot in Montana without having that book open?), the badlands-dominated stretch of territory between Glendive and Dickerson is a mere sample or slice though a huge belt of similarly-formed terrain extending southward until the end of it and northward into Canada as far it goes. Paleocene petrified wood tells us this land was just as lush and wet after the last big comet as it was before, from Hell Creek to Fort Union so to speak. Some Hell Creek clams from the long-lost Interior Seaway. The region is so vast that even the Ice Ages didn’t generate enough ice to scour all of it. It’s been grasslands ever since, long enough that the brontotheres and hyracodons who once roamed it have been replaced over and over. The horse was invented here, leaving a famous trail of equine evolution, but did not survive here, and had to be reintroduced by Europeans. The ancestral camel, llama, and rhinoceros poked around for many millions of years, pursued by inconceivably terrible hyenas, hideously-fanged tigers and dire wolves. There were mammoths. There were mastodons. But it’s been dry for a long time thanks to the Rockies, and there’s nothing left but small game; the bison, the lowly elk, the humble grizzly. Paleocene petrified wood, silicified into agate after repeated massive falls of volcanic ash. Travel sets you up to spot interesting people, if you like that. I have mixed feelings. Donnie is a people-person—a fishing guide would have to be. He lived in various parts of Montana for years, has many friends in the state, and they stay in touch. In his opinion not much was changed in the places he knew, except for the obvious expansion of Billings into a wider town. Donnie sees the landscape in terms of game animals, defined by its rivers; game was scarcer and the land was dryer. When we travel we take our questions with us, and sometimes get parts of answers. Was there a feeling that we traveled in a sort of end moment, seeing the last of a particular America? We’re prisoners of history whether we know it or not. The philosopher Elias Canetti referred to the “crowd of the dead” in Crowds and Power. William Faulkner expressed it well in Requiem for a Nun: “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” Everywhere the model of life for family, folk and nation is the unfathomably heavy hand of the crowd of the past. But people regionally do not have exactly the same dead hand weighing on them. The United States is a cold collation of fairly distinct regions held together by shared cultural concepts. Some of the sharing is involuntary. The culture of what we call democracy has no physical location. As historian Jacob Burckhardt noted (about the Italian Renaissance, in all its artistic instability), powers can be too weak to unify a people but still strong enough to block any other unifying force. Serious academic observations on sovereignty note, in a truly common sense observation, that challenging and being challenged are integral features of sovereignty, or put another way, sovereign claims are always in a state of crisis. Of course, as Michael J. Nelson said in the preliminary skit for Last of the Wild Horses, “There’s a difference between regionalism and just plain stupidity.” Can we have the brontotheres, ghastly giant hyaenas, running rhinoceros and dire wolves back? In no way were we in charge of our own destiny. In the end we turned into tumbleweeds. We saw Lusk, Wyoming, dangling from its long highways. On the side of a windy back road in northwest Nebraska, staring at tufa left behind by an ancient volcanic ashfall, I began to wonder where our home is, not so much in terms of myself as a domesticated monkey, but asking where the life of the body leaves us in relation to the earth. You wouldn’t happen to know, would you? Apparently the literal answer to this seemingly abstract question is “A roadcut in upper west Nebraska.” It feels great to get that answered. Natural home of Moose Drool, possibly the one best beer in the world.

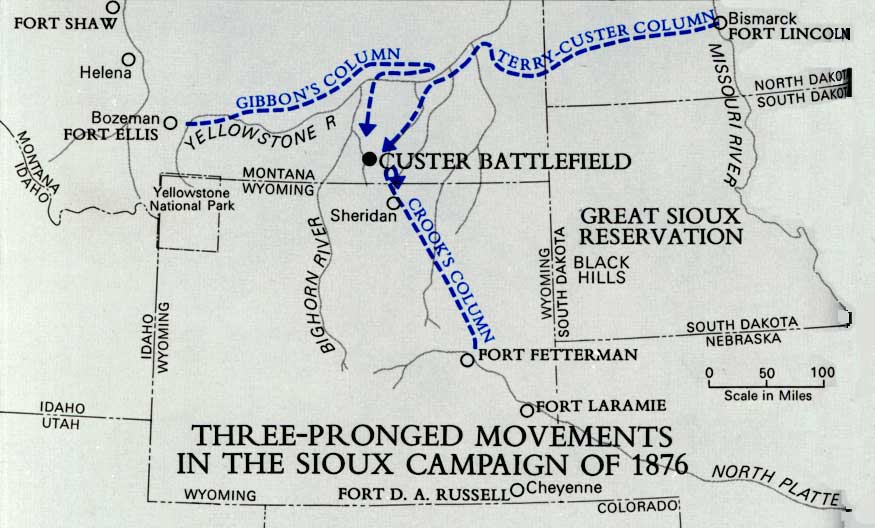

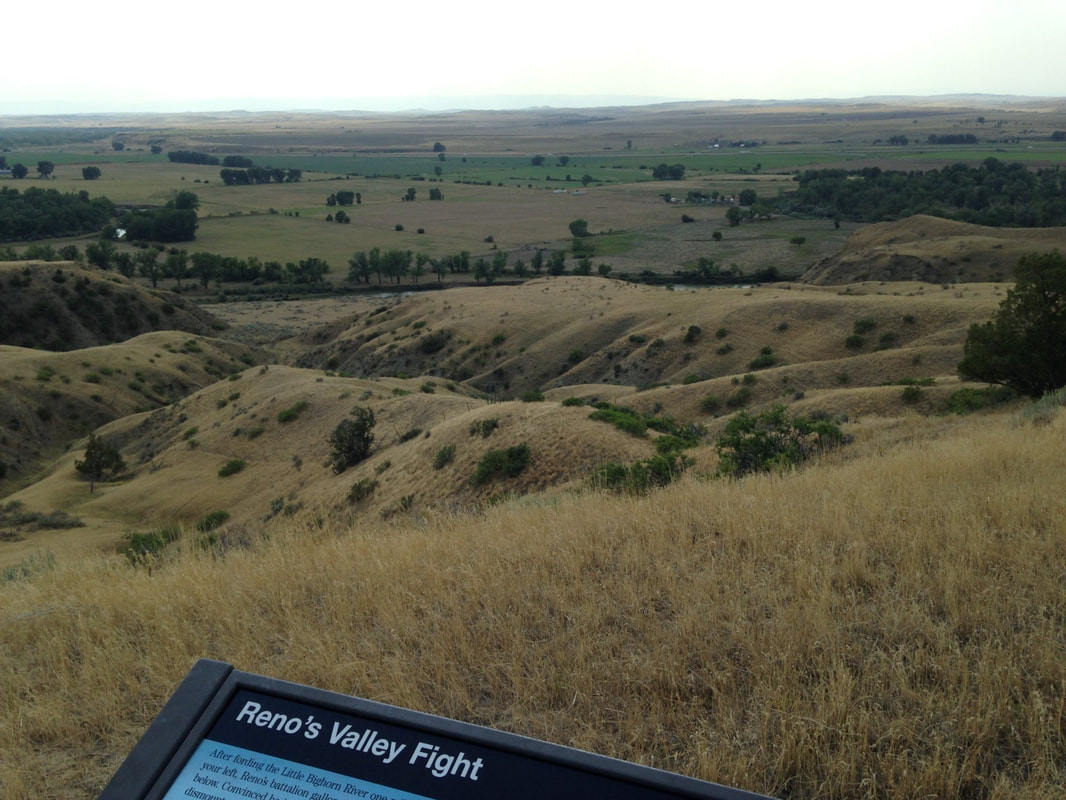

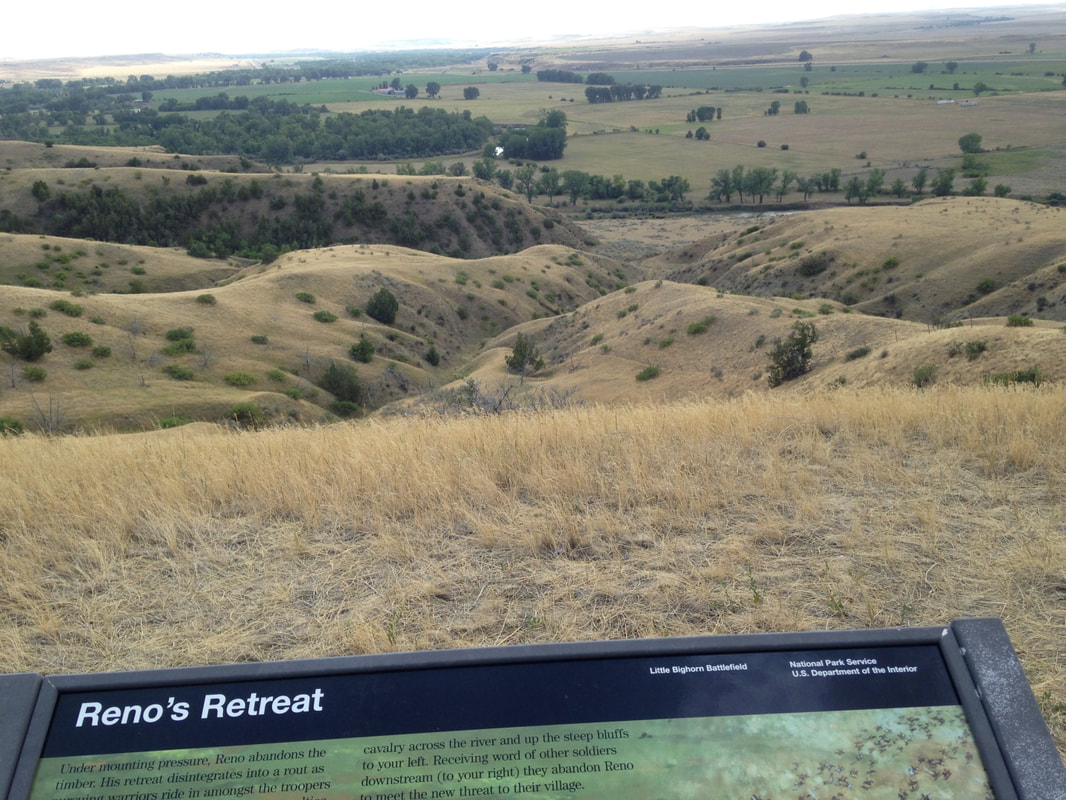

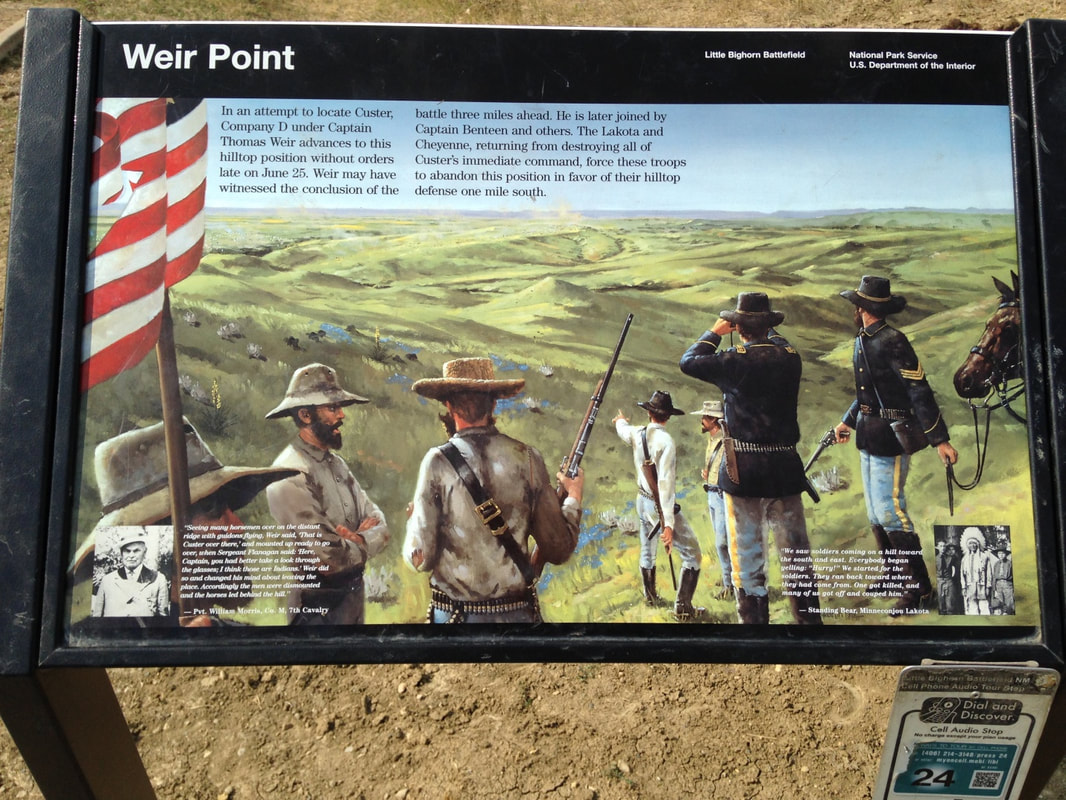

History is what we think about the past, or what someone else thinks. The real existence of the past slides away. When we reach for that story, it slips past our fingers. We’re pulled onward, like all past and future swimmers—maybe a bit surprised at how strong the current is. If history is a river, there’s no bridge to the other side. The Central Montana landscape can be a little hypnotic, rising and falling knolls and ridges in various shades of khaki, waving with grass. In human terms, it’s a sea of names: Native American names, settler names, geographical, geological and administrative names, nicknames and local usages—a blanket of names on the landscape, visible and invisible, sometimes secretive. Deep in this grassland, out on the lone prairie, is the most famous historical name in Montana: Little Big Horn. Over the years, the Battle of the Little Big Horn has bred a torrent of history, fiction, fictional history, film, lecture, essay, legend and myth. It’s not just an American fascination. Most people in the literate world, it’s fair to say, have some awareness of this battle and probably an opinion on it. As a coin of culture or plug-in of connectivity, the Battle of the Little Big Horn is world currency. Why? It’s small for a battle. U.S. casualties were 268 killed and 55 wounded. Sioux casualties are unknown, but the National Park Service considers 36 to 130 to be a plausible range. Custer lost a battle. The Sioux lost the campaign. The campaign was meaningless, because the Sioux were barely surviving, along with the American bison on which Sioux life depended, a singular horror mainly caused by disease, ecological disaster and hunger. No territory was lost or won in the 1876 campaign; the Little Big Horn is on Crow land, and the Crow were on the U.S. side before and after the battle. But this battle was not relegated to obscurity like other battles in the long cycle of Sioux wars. Little Big Horn became a legend translated into every language, a meme, an elevator button to the Sitting Bull and Custer floor. Entry in the Great Events pantheon began almost as soon as the battle ended. Native American witnesses suggest it was an instant legend for the Sioux as well. But that doesn’t answer “why.” Widespread cultural awareness that “a thing happened” is an effect, not a cause. In the end I think we have to answer “why” ourselves, and not agree to be merely told why the Little Big Horn fight mattered—though we can easily see that it did matter. The first people on the battlefield after the Sioux did not find a mystery, but mystery soon found them. Native American Monument, Custer Hill MT. There is no definitive account of Custer’s last fight, and there may never be one. We don’t lack context, however. In retrospect, no power on earth could prevent or even slow the wave of easterners and immigrants pouring over what are now the western states of the United States. When President Jefferson sent Lewis and Clark to explore and claim the upper regions of the American west, he may have imagined the Mississippi River as the reasonable boundary of eastern settlement, leaving the whole of the trans-Mississippi as a vast indigenous territory to evolve in tandem with the rest of the country as time went by. This was soon an obscure notion. Successive presidents devised other land-and-settlement policies, but many hundreds of thousands of individual settler choices created the reality. Depopulation by pandemic was once again the forerunner of migration and resettlement, as it had been in 17th-century Virginia and Massachusetts. European diseases reached the Great Plains before the first white settlers arrived, as Lewis and Clark saw and recorded. Rarely was the spread of epidemics deliberate, though there is the example of Lord Amherst in King Philip’s War of 1675-78. For those of us who might not have access to oral traditions or other forms of heritage subtly linking the present to the past's deep time, no written record exists of the original state of the Plains Indians before the first smallpox waves. We have only flat two-dimensional ideas of that society. Even less likely are we to reimagine the Plains Indians before the adoption of the horse, re-introduced to North America by Spanish colonization. Reconstruction of those lost societies is a job for archeologists and historical ethnographers. By 1876, the year of the Little Big Horn battle, the Native American population had been reduced to remnant bands, survivors of a world-ending plague. The settlers did not worry about this. They died of the same diseases themselves, though not as readily. To them, Indians were part of nature and not the most convenient part. A European-American cultural script for Native Americans was already in place, sculpted by writers like James Fenimore Cooper for the literate general audience. Custer Hill, Little Big Horn, MT. Many defenders gave up their lives. The Sioux, a dominant tribal confederacy, occupied much of the Great Plains. In the north, they were squarely in the path of the already-established Oregon Trail, and in the south they were in the path of settlers aiming to seize the Central Plains themselves. Miners and mining profiteers moved in from the west. St. Louis, easily reached from the entire Mississippi and Ohio watersheds, was an open gate to the Missouri River. The Sioux were already surrounded when the cycle of Sioux Wars began. Hostilities sputtered with regular outbreaks of bloodshed from the mid-1850s until after Wounded Knee in 1890. Why an 1876 campaign, and why Custer? In 1874, the Black Hills belonged to the Sioux, affirmed and reaffirmed in the Laramie treaties. However, persistent rumors of gold led Colonel George Armstrong Custer to invade the Black Hills with a 1,000-strong cavalry column, reaching modern Custer, Wyoming and finding modest quantities of gold. Like Bannack and Virginia City the decade before, thousands of miners and profiteers headed for the Black Hills. The rush led to massive finds of raw gold in the northern Black Hills around Deadwood. There was no U.S. theory that the Sioux could own their own gold. The events started by Custer’s treaty violation soon dispossessed the Sioux. Treaty violations called Federal authority into question, not least the reservation system. It’s hard to be more succinct than Wikipedia about this. “Among the Plains Tribes, the long-standing ceremonial tradition known as the Sun Dance was the most important religious event… Towards the end of spring in 1876, the Lakota and the Cheyenne held a Sun Dance that was also attended by a number of "Agency Indians" who had slipped away from their reservations. During a Sun Dance around June 5, 1876, on Rosebud Creek in Montana, Sitting Bull, the spiritual leader of the Hunkpapa Lakota, reportedly had a vision of "soldiers falling into his camp like grasshoppers from the sky." At the same time US military officials were conducting a summer campaign to force the Lakota and the Cheyenne back to their reservations, using infantry and cavalry in a so-called "three-pronged approach".” The War Department in far-off Washington sought only a punitive expedition. The number of Sioux involved was not large. For the Sioux, this was already a post-apocalyptic summer. Even the buffalo were rapidly being wiped out, an indescribable ecological catastrophe. The Sioux, like all the tribes, were grasping for survival as their world fell apart around them. Not all Plains tribes and leaders responded the same way to the complicated situations they were faced with. These societies, whose social and cultural orders were fully disrupted within living memory, were trying to survive as best they knew. They were warrior societies in permanent mutual conflict. We might think of the Plains Chieftains as somewhat like the heroes of the tribal Greeks in the Iliad, autarchs whose authority rested on heroic charisma. The Plains Indians knew the relationship between power and violence. Some of the lands declared to be Sioux by U.S. treaty belonged to other tribes. The Lakota, for instance, had a history of ignoring Crow boundaries and the Crow had asked for U.S. cavalry help. It was no coincidence that the climax of the campaign occurred on Crow territory. The Crow, Arikawa and others sided with the U.S. and fought in the 1876 campaign as guides and as auxiliary cavalry—a power-based decision. The army deployed three small columns under Brigadier-Generals Crook and Terry and Colonel Gibbon, including hundreds of Crow and other Indians as scouts and allied cavalry. Colonel Custer commanded Terry’s striking force. The combined number of troops in the three columns was comparable to a Civil War-era brigade, minus the artillery. Many were tied up in supply lines and forts. The roadless area over which these three columns campaigned was quite a bit larger—very much larger—than General Grant’s entire theater of war back in Virginia. The map below visualizes the territorial scope and time frame of the Sioux Wars. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_the_Little_Bighorn#/media/File:The_Lakota_Wars_(1854-1890)._The_battlefields_and_the_Lakota_treaty_territory_of_1851_(circa.).png Communication between the Federal columns was incredibly difficult. The Sioux proved hard to locate, but on June 17, 1876, in fulfillment of Sitting Bull’s prophesy, Crook’s column found Crazy Horse and his Lakota and Cheyenne fighters on the Rosebud River. Several hours of hard fighting later, Crook’s Crow allies probably saved Crook’s column from disaster by enabling surrounded troopers to get out. Crazy Horse’s forces then withdrew, and General Crook also retreated. The Battle of the Rosebud knocked Crook out of the fight. Crazy Horse then joined Sitting Bull’s great gathering of the tribes on the Little Big Horn, an encampment celebrating a major religious revival, ceremonially trying to summon the aid and guidance of powers they understood from the universe around them, powers they were familiar with as manifestations of the divine. Calling fervently on the spiritual beliefs of the past in a last-ditch Appeal to Heaven is a natural social response to existential threat. A living witness: Sitting Bull in later life. Source: Wikipedia. As Custer’s column reached the Rosebud battlefield, his scouts discovered the Little Big Horn encampment. This was the goal of the campaign and the climax of the war. Unusual among Federal commanders, Custer had personal experience attacking encampments—in 1868 Custer and the 7th Cavalry had razed Chief Black Kettle’s village while it was flying a white flag under cavalry protection from Fort Cobb. Even the Bureau of Indian Affairs called this a massacre of the innocent. Custer knew how the thing was done and he set out immediately to do it again. We can hardly imagine him acting differently. The column included several Custer family members; the Colonel was accompanied by two brothers, a brother-in-law, and a nephew on vacation. There was also a newspaper correspondent because Custer was already a celebrity with headlines, controversies, fans and haters. The pressure was on Custer to be decisive. Battlefields are the forensic remains of old battles, and speak volumes about what really happened. Generations of scholars, historians and other enthusiasts have spilled ponds of ink about Custer, the Sioux and the Battle of the Little Big Horn. Controversies, theories and reconstructions brew along enthusiastically to this day. There are dedicated specialists in Little Big Horn Studies. The battlefield itself contributes to this fascination. Even if we ignored the many-faceted iconographic status of the Battle of the Little Big Horn in American culture, all the roles the battle has played in the American imagination, and even if we ignored the real causes, purport and issue of the battle, the jewel-like mysteries of the battlefield itself would still remain. There are no definitive versions of the Battle of the Little Big Horn. Richard A. Fox’s Archaeology, History, and Custer's Last Battle: The Little Big Horn Reexamined (University of Oklahoma Press, 2015) comes park-ranger-recommended as a physical survey of the battlefield and its artifacts. The forensic analysis of archeologically-recovered cartridge cases tells a non-theoretical tale. The shell casings discriminate between cavalry and Sioux shooters and can even trace the movements of some of the gunmen across the battlefield. Custer had a large staff and 12 companies at his disposal, a bit over 40 men per company, with 35 Indian scouts, six Crow and the rest Arikawa, for a total of approximately 647 troopers and scouts. One company guarded the supply train. Of the remaining 11 companies, Custer assigned three to Captain Frederick Benteen and three to Major Marcus Reno. Benteen was sent to scout an open flank, and Reno was ordered to attack the southern end of the Sioux encampment. Custer retained Companies C, E, F, I and L. Before he divided his companies, Custer had been told that this was the largest Indian encampment his scouts had ever seen. No doubt it was. With an immensely charismatic leader like Sitting Bull seeking supernatural intervention in a moment of utmost crisis, the Little Big Horn Encampment may have contained nearly all of the last free Sioux. We may as well ask who wasn’t there when Custer arrived. The site of Reno’s attack is the flat middle ground beyond the Little Big Horn. Reno’s attack failed at once. His three companies had to dismount and form a skirmish line. Promptly outflanked, they were next driven into the cottonwoods along the river and finally up the gulches to the top of the ridge, closely pursued. The ridge, however, was not a place of safety. Site of Reno’s retreat. Skyline visibility on the Custer battlefield. The Sioux did not fight in military units under command, but in volunteer bands under charismatic heroes, their skills honed by buffalo hunting. Cheyenne cavalry soon outflanked Reno’s new position and loosely encircled him. Reno’s ridge position was now being steadily sniped at from all sides, and Reno relocated to the area known as Reno’s Hill, on the south end of the battlefield, seen in the photo below. Seemingly from the physical evidence, Reno’s company may not have been given many targets as they were enveloped. Fortunately for Reno and his troops, by then Custer had been spotted on the opposite side of the encampment and Crazy Horse temporarily withdrew from Reno’s positions to repel Custer in the north. Reno’s Hill in the middle distance, in practical rifle range. As Reno’s soldiers hovered on the ridge under fire, Custer’s hard-riding bugler bypassed this area and reached Benteen and his three companies with orders to join Custer. Not long after, Custer sent a second message asking Benteen to hurry up. Benteen, possibly moving toward the nearest shooting, found Reno’s already-mauled outfit instead, and joined Reno inside the envelope. Soon the supply train company arrived as well. Reno now had seven cavalry companies and a supply train inside his perimeter. Rifle pits were dug; there was no other cover except dead horses. Rifle pit on Reno’s Hill. As the Reno fight was developing, Custer led his five companies around to the north, behind the links of ridge that dominate the battlefield. His likeliest goal was to attack the encampment from the north side and capture the fleeing noncombatants pouring out from Reno’s attack. The actual size of the encampment is not exactly known. The National Park Service considers it to have held approximately 7,000 people, with a pony herd of 15,000 animals, and to have stretched for several miles. Estimates of the number of Sioux who took part in the fighting range from 900 to 2,000. The park brochure calls this “possibly the largest-ever encampment of Plains Indians” but we can wonder how large pre-contact Sun Dance encampments might have been, under particularly great charismatic leaders. It’s interesting to learn what the Sioux were shooting with. The bow, the lance and the club remained the main weapons of many Sioux, but archeological shell casings and forensics determined the minimum number of different kinds of rifles fired at various points on the battlefield. Fox’s chart (p. 78) in Archeology, History, and Custer’s Last Battle shows 27 Sharps 50-cal. rifles and 62 Henry 44-cal. rifles on Custer’s part of the battlefield, among a large miscellany of other popular Civil-War-era rifles and pistols. A lot of the rifles carried by the Sioux in 1876 were heavy calibers suitable for buffalo, and the balance of firepower may have been on their side at critical moments. Sharpshooter’s Ridge: one reason Benteen couldn’t risk closing up with Custer. An hour or so into the fight, Reno’s seven companies and all their horses were not yet trapped on Reno’s Hill. Direct attacks were sporadic, sometimes hand-to-hand and suicidal. Pot-shots continued to find targets. Tactics would have called for small local counterattacks to drive off groups of Sioux who came too close. Some of Reno’s casualties died like that. During this dangerous and brief lull, distant volleys were heard from Custer’s position a couple of miles away. Reno cannot possibly have known exactly where that was. Captain Weir, from Benteen’s command, took his company a mile north on the ridge to a spot called Weir Point, and from there he may have seen the conclusion of the Custer fight. Weir Point. Custer Hill on the nearer skyline. Another view: National Park Service Sign. That was the high water mark of the Reno fight. Weir withdrew, and warriors from the Custer fight now descended on Reno’s Hill with new weapons and more ammunition, besieging the survivors until the next day. Reno’s position was appalling, but the Sioux broke camp and moved off when Gibbon’s column and the rest of Terry’s column approached the battlefield. The survivors of the Reno fight were free to ride over to Custer Hill and begin piecing together what happened there. View from Reno’s Hill toward the Sioux rifle positions. Custer’s ideas have to be understood as controlling the battlefield by firepower. His five companies could only bodily control a few acres at a time, but if the riflemen were properly spaced apart, their rifles could freeze or prevent movement for many hundreds of yards. With this in mind, Custer first approached Medicine Tail Ford, across from the part of the encampment occupied by the Northern Cheyenne, Minneconju, Sans Arc, Oglala and Brule. Medicine Tail Ford. Low point on the ridge opposite Medicine Tail Ford. Shooting broke out here. We can draw our own conclusions. Custer’s only imaginable tactical motive was to attack the far end of the encampment and support Reno. But Medicine Tail Ford wasn’t particularly near the north end of the camp. Custer was out in the open, the surprise was over, his foes were gathering under a number of celebrated war leaders, and Crazy Horse, having driven Reno’s command up onto the ridge, was now coming for Custer’s command too. Archeological evidence suggests Custer pulled back to what is now called Calhoun’s Ridge, where he positioned Companies I and L behind a C Company skirmish line. Custer then rode with his large staff, pack of relatives, and Companies E and F around the east side of what would come to be known as Custer Hill, across the area where the Visitor Center, National Veterans Cemetery, and parking lot are now, and then down to the stream bed of the Little Big Horn. Traditionally the Visitor Center and National Cemetery were considered to be off the active part of the battlefield, but cartridge case finds and the dead body of Custer’s newspaper correspondent show that at least some of Custer’s staff got as far as the creek below the cemetery. There they may have finally found the hard-to-spot upper end of the Sioux encampment. However, the entire attack had already failed. Visitor Center, Cemetery, and Little Big Horn seen from Custer’s Hill. I-90 is in the mid-distance. Axis of Custer’s attack is to the right, and axis of retreat is the center foreground. A firing line was formed where the National Cemetery is now (below the Visitor Center in the photo above). Companies E and F stayed for a few minutes and fired a few shots, leaving a scant few cartridge cases as the only evidence. Then, we can reckon, Custer and the rest heard a considerable spate of gunfire in the near distance behind them. During Custer’s excursion to the top of the Sioux camp, C and L Companies were driven from Calhoun’s Ridge to Calhoun’s Hill, rapidly surrounded, and overrun. Archeologically by shell casings and by the accounts of Reno and his officers, who counted the shell cases they saw in 1876, the collapse of this position involved a considerable expenditure of cartridges and the heaviest shooting of the Custer fight. Chief Walks White, or Lame White Man, was killed starting this attack, and here the Sioux suffered most of their casualties, based on oral histories. Warriors led by Gall, Two Moons, and Crow King finished off C, I and L Companies mostly with hand weapons, chasing them “like buffalo,” except for the half dozen or so on the fastest horses making off for the other side of Custer Hill. Grave markers from the annihilation of C, L and I Companies. Custer, on Cemetery Ridge, heard the sound of heavy rifle fire (which was also audible from Reno’s position, and inspired Captain Weir to ride to Weir Point). He would also have heard the firing die down and stop, because the C, I and L Company refugees were mostly being killed by lance and club. A messenger may have reached him—there were some C Company dead next to him on Custer Hill a few minutes later. We won’t know. Horses can move pretty fast, but time was now gone. As Fox reconstructs events from the archeology, Custer, his staff and Company F broke for the high ground of Custer Hill. Most of Company E split off, possibly to block mounted warriors coming out of the encampment onto Custer Hill by way of Deep Ravine. E Company was destroyed at once. A handful of F Company, Custer and staff got as far as the markers where they fell. The entire Custer fight took roughly half an hour and the Custer Hill climax may have been over in minutes. By this reading, Custer died in mid-maneuver as his command disintegrated around him. The next day, June 27, Reno's survivors reached the scene of the Custer fight. Captain Benteen later reported: "I went over the battlefield carefully with a view to determine how the battle was fought. I arrived at the conclusion I [hold] now—that it was a rout, a panic, until the last man was killed ... There was no line formed on the battlefield. You can take a handful of corn and scatter [the kernels] over the floor, and make just such lines. There were none ... The only approach to a line was where 5 or 6 [dead] horses found at equal distances, like skirmishers [part of Lt. Calhoun's Company L]. That was the only approach to a line on the field. There were more than 20 [troopers] killed [in one group]; there were [more often] four or five at one place, all within a space of 20 to 30 yards [of each other] ... I counted 70 dead [cavalry] horses and 2 Indian ponies. I think, in all probability, that the men turned their horses loose without any orders to do so. Many orders might have been given, but few obeyed. I think that they were panic stricken; it was a rout, as I said before." I hope that was a refreshing account of an old battle, but it occurs to me nothing in it says why it matters. But we know it did. Little Big Horn is a tangibly spiritual space, not just the site of an incident in the Great Sioux War. The nature of places has never been something language captures well. The ancient Greek belief in daimons of place or landscape remains compelling to me. Donnie offering tobacco at the Spirit Tree on Custer Hill. Whether a Spirit is its own power, or has power conferred, and whether the world is a conduit for Spirit, are questions I cannot answer. A Spirit is a Thing; what we are most looking for would come from beyond the world of Things and Spirits. Perhaps Sitting Bull’s powers were real. Maybe he summoned something that has not yet entirely departed. At least that would help explain the weird story of the Little Big Horn grave markers. Reno’s command had already left a trail of graves across the battlefield before they reached Calhoun’s position and the first bodies. All the bodies on the battlefield had been mutilated, which the ancient Sioux did both for revenge and to release the angry spirits. Also everything of the least value or use had been stripped and carried off. One witness remarked that no horse equipment of any kind was left behind, “not even a strap.” The bodies had been in the sun long enough to swell up, and most were unrecognizable. The troopers buried them where they lay, in very shallow graves marked by stakes, sometimes scooping the dirt over the body from both sides in a low mound, and sometimes covering the barely-scraped graves with brush. They had a long string of burials to perform, all the way to Custer Hill and Deep Ravine, and they were exhausted and shot up and tending to over a company’s worth of wounded. It wasn’t the best job. A year later, in 1877, the army mounted a reburial expedition. The graves were exhumed and re-interred, and the officers’ remains were taken back for their families to dispose of, including five members of the immediate Custer family. But this wasn’t enough. Another expedition to repeat the performance and further improve the Little Big Horn burials was sent in 1879. That wasn’t enough either. A more fully equipped expedition in 1881 moved all the relocatable remains to a mass grave at the top of the hill, and installed a granite obelisk. They also re-marked the original grave sites. Obviously that, too, wasn’t nearly enough, and in 1890 Captain Owen Sweet and company arrived with 246 individual marble markers for the original grave sites as best he could determine them. To quote Fox, “…Sweet incorrectly placed on Custer’s battlefield 44 markers intended to memorialize Reno’s dead.” The 1881 obelisk. Moving ceremonial rocks around has always been a pretty sure indication that something’s going on, as far back into the deeps of human history as we care to go. Compulsive ceremonial rock-moving suggests acute spiritual disturbance of some kind. Obviously these were not the restful dead. These were some hot dead. Bone juggling is another old-timer method of spiritual invitation—one sees it in places like Amiens and Rome—Verdun, come to think of it, is a modern example—but it’s really one of the older magics, like moving rocks around. There was much juggling of Little Big Horn bones. Make of that what you will. Sweet’s placements, when you’re on the field, subtly tattoo the landscape. They’re artistically placed in an Aesthetic Era fashion and we are reminded that an 1890 cavalry captain is a civilized man. He stayed within the constraints of the original burials but counted depressions as former graves. Thus, where dirt had been dug out from both sides to mound the body in a shallow grave, Sweet counted that as two graves. Twin graves appear prominently here and there. In the Ruskin-inspired esthetic appropriate to the period, the overall pattern of placements would be unthinkable without these twinned stones. In a way they mark the original locations of the worst-buried people and in another way they save the whole pattern from mere naturalistic formalism. The Spirits love these dual meanings. The deeper meaning goes past spirit. The pattern of the grave markers on the Little Big Horn battlefield is not exactly an accident. Contrapuntally we can ask whether the markers do or do not amount to coincidence. If we go with coincidence as an explanation of the pattern, then it’s a large one. A twinned grave from the C-I-L Company fight. Custer Hill is in the background. In the 20th century the Park Service still heard unmarked graves calling to them, and placed six more markers. Eventually the tribes who helped create the original layout brought more good ceremonial stone, and the heart-rightness of these installations shows they actually were needed. I wouldn’t like to guarantee that we’ve seen the last of the rock-moving on the ridge, even now… Where they fell. US 212 in the background.

In 1862, a group of disappointed gold miners roaming through southwest Montana stopped to pan Willets Creek (as named by Lewis and Clark). The miners called it Grasshopper Creek. They struck gold, and it was one of the big strikes that reverberated with a thrill all the way across the continent. The first lucky miners wanted to keep it secret, but as more and more fine gold turned up, desperate and heavily armed men showed up by the thousands. Thus Bannack was founded as Montana’s first capital city. The shootin’ and buryin’ started immediately.  Early resident of Boot Hill, Bannack MT. The ghost town of Bannack, view from Boot Hill. In an earlier installment of this series I mentioned “numbers” next to disease as one of the immediate causes of the Plains Indian apocalypse. Gold and silver explain the numbers. Miners and their hangers-on flooded in. The surviving ghost town of Bannack is the core of the older settlement; at its peak the valley in the photo above was covered with shacks, extending up all the nearby creeks and rivulets. The climax of the Sioux War was more than a decade away, and far to the east; associated with another gold strike, in the Sioux treaty lands in the Black Hills of South Dakota. Numbers. The white migration into Montana and the Dakotas knew no borders. At the end of the Civil War, this population movement soon became more sudden and definitive than the tribal migrations of the Goths or the Vandals. The East, having succumbed to a racialized politico-military convulsion and the economic and moral collapse of the defeated Confederacy, spontaneously vomited war across the full length of its frontier. Desperados, outlaws, treasure seekers and failed men of every description, along with madly optimistic immigrants, sometimes whole families, swarmed west. To some extent territorial seizure was regulated by U.S. cavalry units left over from the butchery in the East, but the invasion itself was composed of civilian hordes; the professional cavalry were the wagging tail of this mass migration. By no means were all the newcomers land seekers, and many did not intend to stay in the West. Many were seeking treasure in the ground, while others were seeking their treasure at gunpoint on the road from the mines. Thus Bannack, a very salty hellhole in its day—so disorderly that some of the details of its history are composed of conflicting accounts. Beaverhead County Courthouse, built in 1875, later converted to a hotel. Vernacular architecture, Bannack. The ambiguous saga of Sheriff Henry Plummer says much about life in early Bannack. First, though, it’s important to remember that Bannack lasted as a steadily shrinking high desert shantytown far into the 20th century, until the last resident left in the 1970s. "Sputnick": 1960s dredge mining equipment, Bannack. Sheriff Henry Plummer couldn’t have foreseen Sputnik. Hell, he didn’t even foresee his own hanging, even though he was the one who built Bannack’s first gallows. Bannack’s great blessing, gold, was the problem. Gold shipments regularly disappeared, leaving only corpses behind—over a hundred victims just from gold robberies alone, not including the other roughhousing going on. And there the story splits. Either the sheriff was named as the head of the gang by a murderer on the gallows, or else he was caught red-handed with his deputies. Either way he suddenly wound up with a rope around his neck and there the story splits again—he either claimed innocence and asked “for a good drop” or else offered to return “a wagonload of gold” if the Vigilantes would spare his life. Which they did not. We’re free to imagine Henry Plummer’s stolen gold out there under a rock somewhere, which would be a magnificent ending. Remains of authentic red velvet wallpaper from the old days of Bannack, later papered over with a more sedate pattern. Dry air preserves Bannack. Wandering the halls: Hotel Meade. Bannack’s old saloon bears mute testimony to whiskey. It must have taken many years for Bannack to calm down. Meanwhile, the territorial capital shifted to Virginia City after the enormous Alder Creek gold strike there. Geology once again made its weight felt politically. Life was wilder if anything and southwest Montana was briefly ruled at gunpoint by the Vigilantes, who were not necessarily universally popular. Neither was what passed for the law—the massive timbers of Bannack’s old jail are riddled with bullet holes. Bannack's original jail. Scarred. So ornery they had to chain them to the floor: jail annex, Bannack. Virginia City circa 1868. https://westernmininghistory.com/towns/montana/virginia-city/ Geologically, ghost town Bannack is off the highway, unlike Virginia City and adjacent Nevada City, which survive as important roadside attractions. Virginia City, MT. The word “anarchy” is often a synonym for mad disorder and violence. Philosophically, though, anarchy is better described as a highly individualistic social system prizing personal autonomy above other social values. It’s a concept closely tied to “autarchy,” a social system (or part of a multi-tiered system) where the most socially elite, typically the richest or most powerful, are excused from the effects of law. Obviously much more could be said, especially in the academic context. It’s worth noting occasions where odd social systems like classical anarchy emerge briefly as founding conditions. Colonizing situations where a new population violently substitutes itself for a previous population seem to provide opportunities for considerable legal fluidity. NEXT BLOG: POLITE FICTIONS

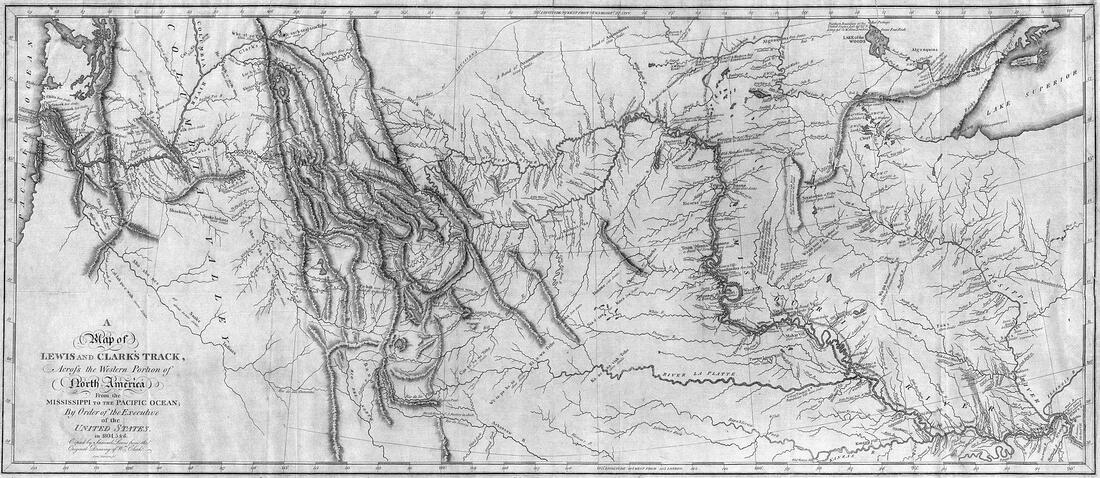

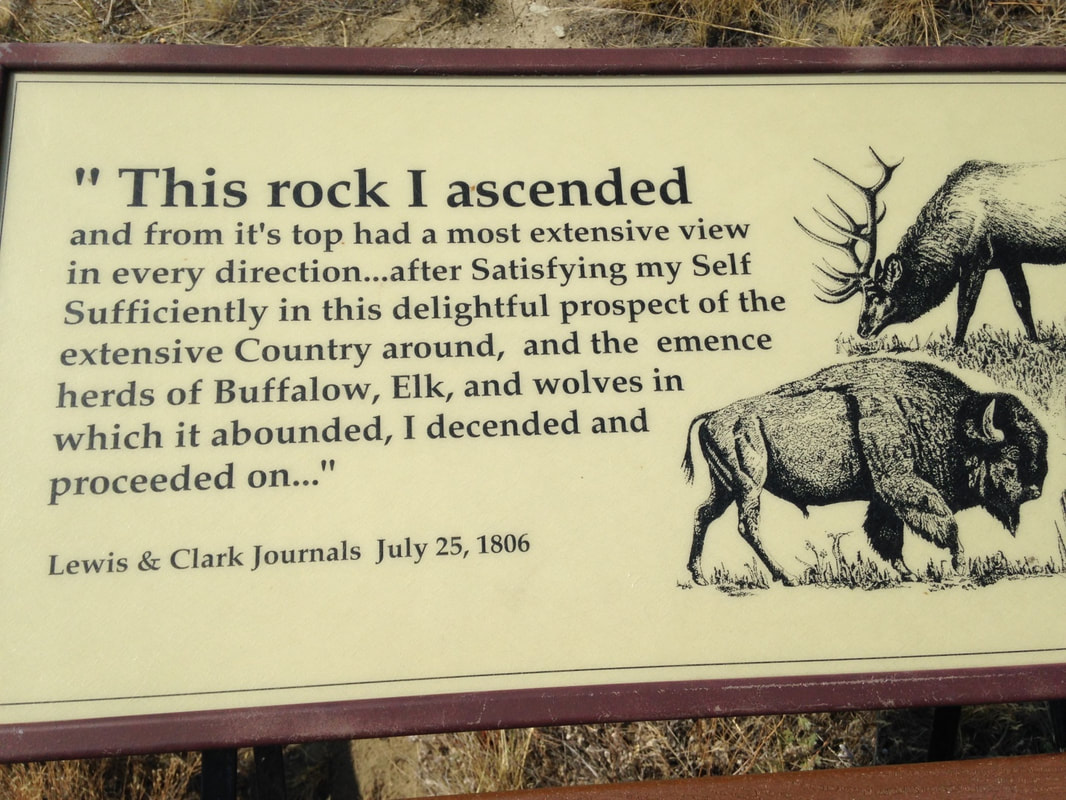

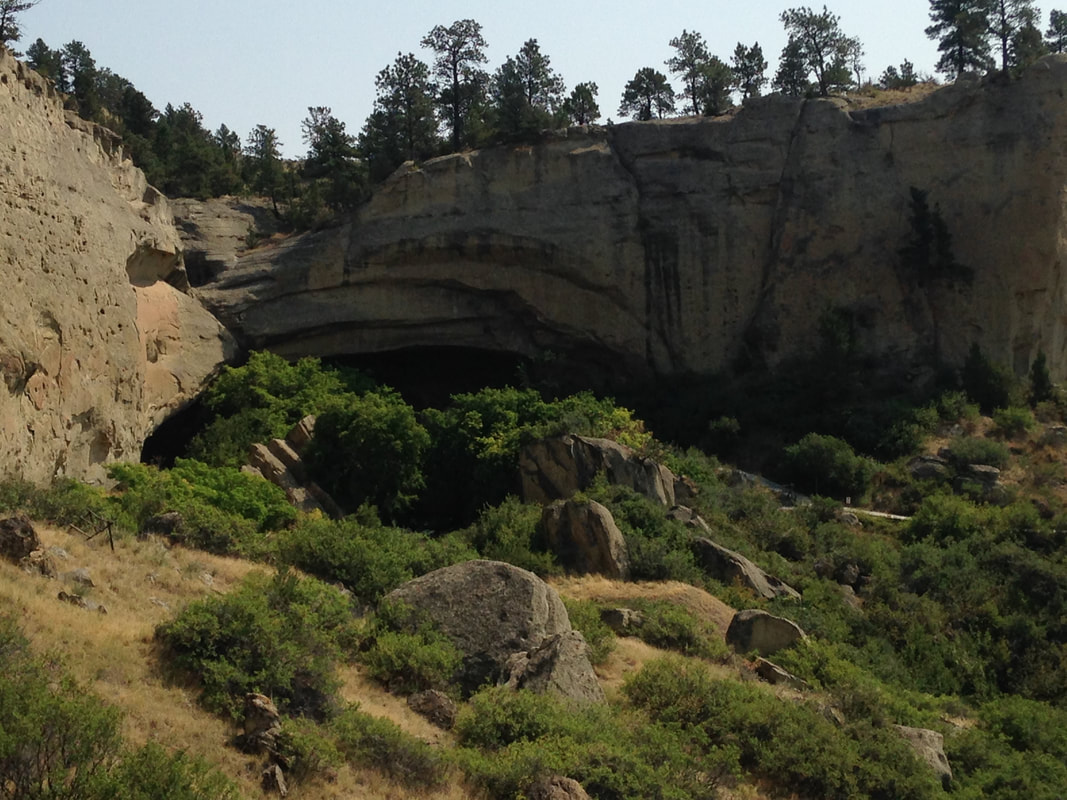

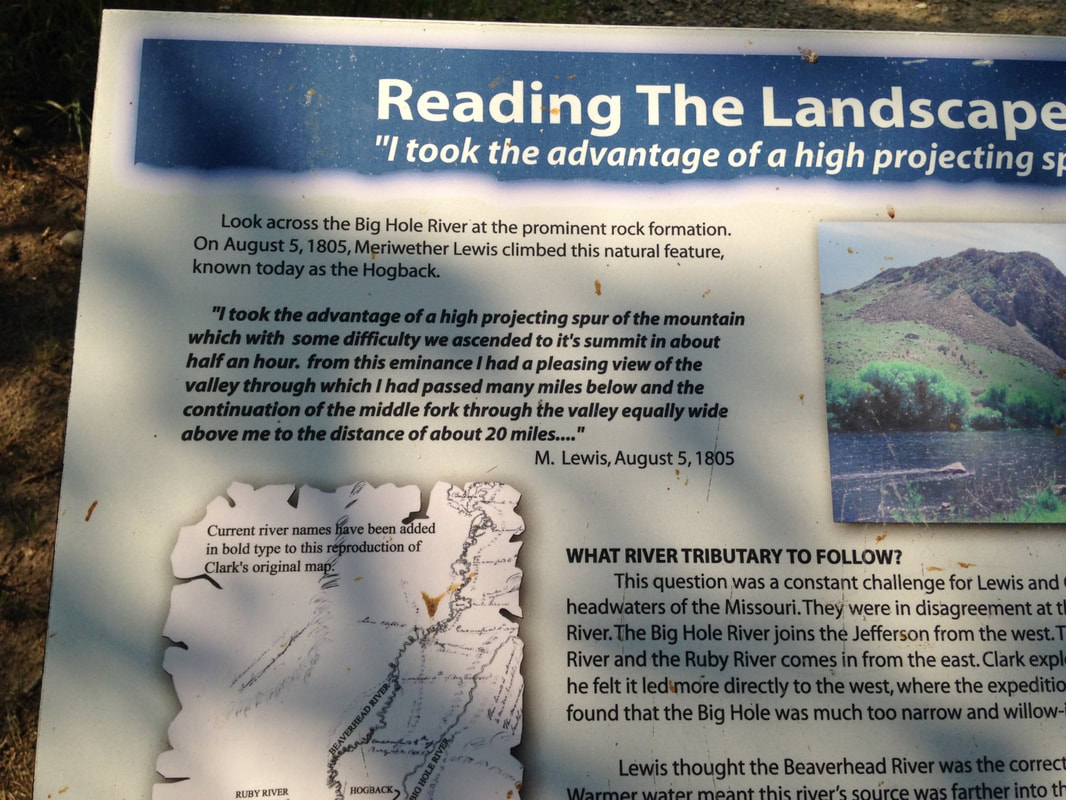

Should driving all the way across Montana entitle one to vote in Montana? It’s a long way across. I know nothing about Montana politics. I assume there are some. If the Montana legislature extends me a vote, I would vote Labor. I read that cattle are still king, with nearly 3 cows per person statewide. Copper, coal and oil also count for a lot. Montana is infused with minerals. It’s not a poor state though plenty of poor people live there. Our route picked up the trail of Lewis and Clark on the Missouri River in North Dakota, and we were repeatedly on the track of their expedition all the way to Dillon, Montana. Lewis and Clark's map. Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=499383 People traveling on foot gain a striking familiarity with their surroundings. That helps explain the astonishing liberty Captain William Clark took on July 26, 1806, during the return journey eastward, when he carved his name and the date near the top of Pompeys Pillar, a sandstone landmark on the banks of the Yellowstone, as a territorial claim on behalf of the United States. Pompeys Pillar is a historical sacred space called “Mountain Lion Lodge” in the Crow language, and many petroglyphs had already been painted or carved there over the millennia when Clark arrived. Pompeys Pillar. Clark chiseled the first white cartouche on a sacred ancestral rock in a place more utterly mysterious than Coleridge’s Xanadu at the time. Many later travelers would do the same. We should probably conclude that the Crow took Clark for some curious and genial freak of nature, dragging expedition boats and provisions, shedding gifts, leading a gang of miscellaneous followers from beyond the beyond. They could not have known Clark’s petroglyph was actually a seal of doom. Nor could Clark have imagined such a thing. The sign reporting what Clark wrote about the view from Pompeys Pillar. View from the top of Pompeys Pillar, August 2021. Sixty-nine years and eleven months later, almost to the day, Custer’s 7th Cavalry Regiment took a legendary mauling at the Little Big Horn, not too far away as distances are reckoned in Montana. If seventy years does not seem long enough to get from Clark in 1806 to the Sioux campaign of 1876, consider that Montana’s first capital, Bannack, was founded in 1862, only 56 years after Clark engraved his mark. Within the span of an ordinary lifetime the Plains societies were overrun and the land claimed by an alien civilization. Rock shelter at Pictograph Cave State Park, near Billings MT. The history of the Plains societies is truly ancient and yet largely unknown. Native Americans were following the buffalo on the plains at least 10,000 years ago, long before the pyramids, long before Ur. The Plains cultures were revolutionized around 1700 CE by the return of the horse to North America, but their roots were much older. Pictograph Cave and other adjacent rock shelters were sacred ceremonial places for Plains societies at least 5,000 years ago. One feels this estimate is far too short. Most of the pictographs here were lost before conservation, but archeology at the site has recovered over 30,000 artifacts. Nearby Ghost Cave seems to retain the memory of a haunted reputation. Such places remind us of what we do not know--about the passage of time, about the life of humanity.  Ghost Cave: memories of ceremonial power. Interior of Ghost Cave, a sandstone rock overhang. On their outward journey Lewis and Clark followed the Missouri into the Yellowstone near the North Dakota state line. Quite a while passed before the Rockies came into view near modern-day Billings. They were following the largest river system in North America.  Jefferson River and Tobacco Root Mountains north of Dillon, MT. After hauling upstream as far as the Tobacco Root and Ruby Mountains the members of the Expedition certainly knew they had come awfully far across what would later be called Montana. “Both Capt. C. and myself corrisponded in opinion, with rispect, to the impropriety of calling either of these streams the Missouri and accordingly agreed to name them … we called the S.W. Fork, that which we meant to ascend, Jefferson's river in honor of Thomas Jefferson. the Middle fork we called Madison's River in honor of James Madison, and the S.E. Fork we called Gallitin's river in honor of Albert Gallitin.”—Meriwether Lewis. Soon they were naming various headwaters after the elusive pillars of Thomas Jefferson’s character, Wisdom, Philosophy and Philanthropy. These names did not stick, but the Native American names were also lost. The Wisdom, Philosophy and Philanthropy Rivers are the Big Hole, Willow Creek, and Ruby today. Meriwether Lewis went up the Big Hole, or Wisdom River, trying to get to the Pacific divide. This route soon lost its promise, and Lewis had to climb, to understand the real lay of the land. Soon after the Big Hole failure, Lewis and Clark chose the Beaverhead route to cross the Pacific divide. Obvious in the end. The Hogback: A massive exposure of Paleozoic sandstones on the Big Hole River. In some ways the stretch of journey around Dillon seems like the real climax of the Lewis and Clark story. Here Sakakawea was reunited with her brother, Cameahwait, on the side of US 41 in the shadow of Beaverhead Rock. Beaverhead Rock looks so much like a beaver head that the idle tourist today can imagine her shock of recognition. Some miles upstream the site of Camp Fortunate, where the Expedition got its first horses, lies drowned under the Clark Canyon Reservoir. As Donnie pointed out, the Big and Little Buffalo Rocks south of Dillon are indeed almost eerily bison-shaped, just as Sleeping Elk Mountain is remarkably shaped like a sleeping elk. Later we found Mountain Lion Rock, which could not have been any more obvious if it had been put there deliberately. Other important landmarks are strewn liberally across the region, their significance only vaguely recalled, once part of the Native American landscape system, more associative than ours, in which sometimes things are what they are, not merely where they are. Donnie knows these legendary trout rivers very well from his years as fishing guide working out of Dillon. Sometimes it’s valuable to go back and see the important places in your life again. Dillon, population just over 4200, did not show the fishing activity Donnie expected to see. Concerns about smoke from the fires, Covid, and drought probably affected the local trout season. Some rivers were closed to fishing. The drought is real. Covid is a disaster, and the smoke from burning California hazed out the view of the Rockies. There was fishing activity on the Madison, but basically this sport-and-tourism corner of Montana is obviously hard hit in 2021. It was interesting in Dillon and later in Virginia City to see what was closed on Mondays and Tuesdays versus Tuesdays and Wednesdays, or if the owner was working the counter from labor shortage. The sudden and near-complete loss of rental vehicles also cuts deep. To go to Dillon, you have to have something to drive. Walking remains impractical over such distances, despite the example of Lewis and Clark. Not far from the strangely deserted trout fishing put-in where Lewis climbed the Hogback on August 5, 1805, the Nez Perce exiles stood off the U.S. cavalry for the last time at the Battle of Big Hole on August 9-10, 1877. The tragedy of the Nez Perce, driven from the Pacific Northwest onto a reservation in Idaho, then escaping into the Montana ranges in search of allies or at least a place they could defend, was the next-year sequel of the 1876 Sioux campaign. We must add this to our haunted reckoning of the Native American apocalypse. The strategy and planning behind the 19th century cavalry campaigns in the West seem haphazard in their details. Aficionados of Civil War studies won’t recognize the same Grant and Sheridan, Crook or Custer, the same Major General O.O. Howard or Gibbon. The tactics seem clumsy, colonial, below military grade. The officers themselves thought so too—they spent much of their time making excuses for failures, casting blame, and trying to cover up grotesque mistakes. “What did they know and when did they know it” was an 1877 press meme. Somehow, corruptly, military operations in the West were a public scandal. It takes a second round of thinking to recognize that, despite the flags and the bugles, the context of these operations was not actually military. The Native Americans had already been absolutely and utterly defeated long since. The cavalry firepower was for policing reservations. Catching bands of escapees was the only strategy needed, in a pattern going back to the Dakota War in southwest Minnesota in 1862. It was already obvious that disease and numbers had settled the land tenure question. The Plains societies collapsed like bubbles. When Lewis and Clark reached the Mandan lands in 1805, they found freshly desolated villages and a smallpox epidemic in full swing. Eastern diseases would sweep through the Plains repeatedly in the decades that followed, a pattern seen in North America since the first Spanish landings and settlements in the 1500s. www.ndstudies.gov/gr8/content/unit-ii-time-transformation-1201-1860/lesson-4-alliances-and-conflicts/topic-1-smallpox-epidemics-1781-1837-1851/section-3-smallpox-epidemic-1837 The final fatal blow to the Plains societies—the annihilation of the bison herds—came late and seems almost unnecessary. At that point the Sioux had already been reduced to a trapped remnant But bison are dangerous and cows aren’t. Clearly settlers with cows needed the bison to go away too. The landscape seems somewhat haunted by its historically recent human and environmental apocalypse. Facts about history are often facts about the present as well. The vast migrating herds of bison and elk were not replaced by vast herds of cows. Cows are far too expensive to risk any sort of surplus. Driving through Montana, I could not help fantasizing about putting the bison, elk and wolves back. As wild animals, they might very well support themselves, which cattle cannot do. We approach landscapes through names. Sometimes the name we use has an older name behind it. Native American names are strewn across the landscape intermixed with settler names. Sometimes the stories explaining the settler names are as forgotten or mysterious as the Indian names, already with one foot in the world of ghosts. Ghosts. Last relics of a miner’s shack, 1870s-1900. High desert. A McKinley-era ranch house lost in the sagebrush. In the main, though, landscapes are sensitive to much more than mere human history. Volcanic intrusions along the seams of sedimentary rocks in the Montana ranges left deposits of gold, silver, copper and other valuable metal ores, recognizable by their characteristic suites of intruded rocks. Around Dillon the landscape vividly recalls this happening at least twice, in the later Cretaceous and then again in the Eocene. Many a miner was dry gulched. Intrusions. Lava intrusions were a side effect of the western Montana tectonic train wreck that lifted and displaced gigantic regional chunks and carried them for many miles off to the east, double-stacking the landscape. As the great overthrust progressed, plate subduction drifted farther in the direction we now call west, as new sheets were piled up against the rising Rockies. Even the gap Lewis and Clark used to reach the Pacific Basin is a relic of the old remembered days when the Beaverhead River ran briskly off to the nearest sea, instead of being hoisted up and tilted off towards the far end of a still-growing continent. All the Expedition’s newly renamed rivers were divorced from their original ocean and since remarried. Not the sort of thing a real landscape forgets very easily. It explains a lot, locally and also in general. NEXT BLOG: ANARCHY IN BANNACK

“…the only thought which comes to me is a feeling of their isolation…” Arthur Conan Doyle, “The Adventure of the Copper Beeches.” Describing the land tracts, leases and public lands of eastern Montana would not convey a sense of presence. One cannot conceive the life and society of the High Plains by driving through. Fortunately my traveling companion and cousin, Donnie Mawyer, spent decades as a hunting and fishing guide and occasional cowboy in Montana. Montana is the big leagues for fish and game, with vast sprawling Pleistocene landscapes and literally legendary fishing rivers like the Madison and the Jefferson.  Donnie Mawyer on the Little Big Horn. The guide has to be a naturalist, pack animal and boat handler, gun and rod expert, wilderness navigator, camp host, and much else besides. You have to like animals and you have to like people, and in the end you have to be able to sight an East Coast banker in on an elk four football fields away, and then finesse your banker into actually hitting his elk. Understanding how important the trip and the trophy are to the client was Donnie’s most special skill as a guide. His sensitivity made him a celebrity guide and sensei of other guides. Then there were the necessary jobs of convenience to fill in the off seasons, because even a very good hunting and fishing guide still has bills to pay. Cowboy life is rough stuff even when everything goes as well as could be. Throw in a few horse wrecks and bull stompings and no wonder the old cowboys in the old bars in remote towns in Montana appear physically and emotionally mangled. There’s nobody going to come up to these old prairie salts and say “Damn glad you did that to yourself—what a terrific choice.” Just to vary the possibilities, let an oilfield or two spring up in the local geology and you can add being worn down by heavy machinery to your resume. An iron grasshopper. Baker Oil Field, Wibaux Co. MT. A far-flung road north of Wibaux. The guide and game situation in Montana is not as easy as it was. There is less game and the rules have changed. The world has changed. The situation for ranchers, who are the responsible society of this part of the High Plains, is also not getting better. We knew about the drought before we went. It is severe, as is the fire risk. We learned the 2021 price of hay for the winter has shot up 300%, and this will probably sell out some ranchers. These details could have been guessed in advance, very Adam Smithianly. The grasshoppers, however, were a surprise. So many grasshoppers were plastered to the front of my car for the rest of the trip that I did not think to take any grasshopper photos. I regret it. A multi-generational grasshopper infestation was in full swing in Wibaux County, enough for the locals to feel the economic impact. I guess I can check “locust plague” off my bucket list the way Don’s old doctor and lawyer clients checked off “elk,” “grizzly” and “mountain goat.” Wibaux, MT. Population approximately 600. The corner of Main and First Street, Beach, North Dakota. Population just over a thousand. Clearly these High Plains towns have been larger and more prosperous than they currently are. It’s quite obvious that there was once more to these places. It’s as if a certain pattern of early 20th century town and community growth was broken off, and then resumed in a different 1960s pattern, resulting in the newer town or village growing out as a weak appendage of the now nearly dead historic core. This, I think, is what it looks like. The most obvious explanation to me is ghosts. We living beings flounder around with very little concern for the dead and the spirits of things around us, and where people are thin on the ground the situation is emotionally not too stable. Old railroad hotel and open invitation to get haunted. Dillon, Montana. Modernity is the interstate. The larger towns have interstate exits with gas and convenience stations, fast food and motels. Dickinson, where we stayed three nights, is large enough to have a dead mall, but too small to overpower its exits, which have come to dominate the town so neatly split down the middle. However, an interstate exit equals jobs. A big cluster like Dickinson equals quite a lot of interstate service jobs. It’s not nothing. The population of Dickinson, ND is over 25,000. It’s the regional capital. The next regional capital west of there is Glendive, MT, population about 6000. Glendive’s a good place for a Creationist museum. It’s pretty clear the population is mainly composed of Dissenters—all kinds. It’s dissenters and more dissenters all the way. Blame belongs to Easterners for all the things there are to dissent from. Viewed from the High Plains, the Easterners are very obviously in charge of the world, and they’re not doing a very good job. The High Plains and the High Desert are on their own and they know it. This reminds to me ask who the last Western president was. Nebraska: Gerald Ford. LBJ was a Texan but then we have to speculate whether Texas is part of the rest of the West or somewhat like a different country. If Kansas is west enough, then the answer could be Eisenhower (also born in Texas though). California is not the west, it's the coast. There has never been a Mountain West president. It’s possible that as a nation and as a people, so to speak, we could do with a crack at that. These are the people, and agriculture, specifically the ranches, remains the chief economic and civilizational explanation for life on the High Plains. This despite the Billings refineries, a brief hydrocarbon boom and the reasonable expectation that there will be another. The stick-togetherness is about farming and cattle on these vast expanses. An active social life requires burning a lot of gas. And success on the ranch requires equipment. A combine harvester can cost half a million dollars. Being a rancher is like having several largely entrepreneurial full-time jobs at the same time. Prosperity hangs by a thread. But I speak as a retired editor, the most ruthlessly unprosperous profession in America. So on some levels these guys are pretty lucky. And they have the Badlands. And the K-T Boundary, and the mass extinction that ended the Mesozoic. And the ever-looming possibility of that dinosaur jackpot. Like Dinosaur Dan, living in a trailer with thirteen children, hitting a multimillion dollar T. rex and, two divorces later, very nearly half-ruined again. I did not meet Dinosaur Dan. A guy deserves some privacy. You need privacy to be a legend, and Montana can still produce legends. I need privacy. Hard rock on the anticline, Wibaux County. Steeper than it looks. A glorious honey-gold sandstone. NEXT BLOG: ANOTHER SIDE OF MONTANA

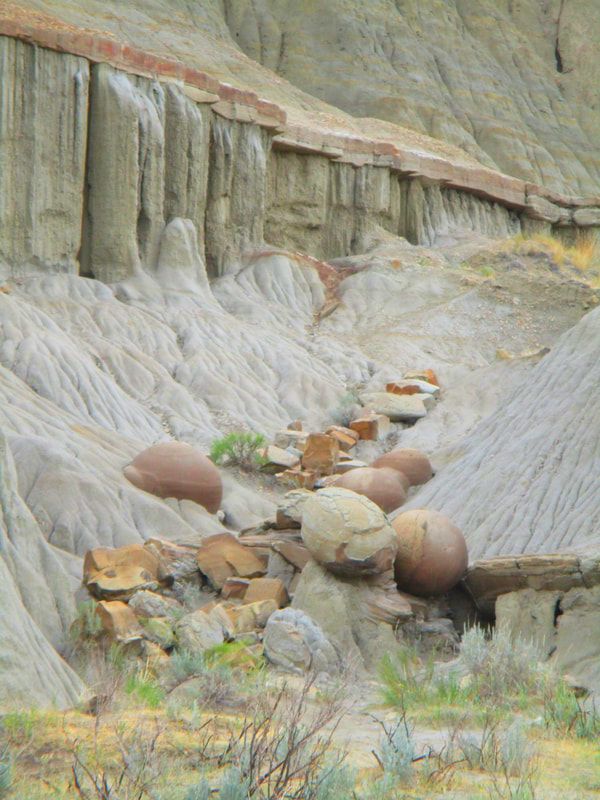

With fire, floods and Covid raging, could there be a better time to explore America? It seems to me we are surrounded by history in the making, because I don't believe the US is going to return to the conditions and circumstances of 2019, in retrospect...  "Speak no evil": one of three tree trunk yard monkeys outside Latrobe PA. "Let's go visit history," my cousin Don suggested. Don is a retired hunting and fishing guide, and our main objectives were eastern and southwestern Montana, the principal scenes of Don's wilderness guide career. Yellowstone was planned next, then a return drive through southeastern Montana, visiting the Little Big Horn battlefield and Wounded Knee. In the end we went farther than we meant to go. Montana is a huge state, about 70% the size of France. Every state in the Union is eventually measured against the size of France for quick comprehension, a meme that will outlive us all. Apparently France is why the chicken crossed the road. Seemingly no one ever questions our understanding of how large France is. Unable to fly and then rent a vehicle, a national situation caused by the combination of Covid and economic brittleness, we could only drive. No longer were Pennsylvania, Wisconsin and Minnesota flyover states; they became drive-through states. It's unfair; these states are replete with weird little features and points of interest. But the interstates only allow a distant glimpse. At the end of the third day of our trip we reached Dickinson, North Dakota, and considered our journey to have properly started. Approaching Dickinson, ND from the visitor center on I-94. The hero of the southwestern North Dakota badlands is the Fort Union Formation, composed of Paleocene mudstones, lignite and brick, lying over similar mudstones and shales of the dinosaur-rich Hell Creek Formation. The Cretaceous Hell Creek Formation is separated from the Paleocene by the iridium-rich K-T Boundary, which marks the asteroid that killed the dinosaurs and ended the Mesozoic Era. This was a big event in earth history, but in North Dakota and Montana it did not apparently affect the inland sea/lagoon morphology of the landscape very much. Deposition went remorselessly on. The North Dakota Badlands: From the Painted Canyon Visitor Center on I-94 west of Dickinson. The magnificent Theodore Roosevelt National Park (TRNP) displays the badlands gloriously. The two units of the TRNP are intricate mazes with hard-surface one-way roads maintained by the Park Service, connecting to hiking trails and scenic walks. The two units are about 60 miles apart. The northern unit is well away from the interstate, features the upper waters of the Little Missouri River, and is more deeply cut. Valley of the Little Missouri. These clay formations are carved by water, and slumping is the main erosional form. The TR has spectacular examples of the kinds of iron nodules that form in such settings, originally as algal/bacterial gels at the bottom of what must have been somewhat stagnant lagoons. Cannonball nodules, North TRNP. Eroded gulch with cannonball nodules, North TRNP. Both units of the TRNP have lots of wildlife: a bull bison looking into the window of the car. Bison in the South Unit, posing for nickels. Sage, prairie dogs, bison, turkeys, mule deer, antelope and countless other things milled about the TRNP in profusion. A painter or photographer might easily go insane in there. As Don said, most national parks are embedded in the present as preserved and protected lands. But when you look at the Theodore Roosevelt, it's as if you're looking back in time. Striated clay mudstones, with bison herd in the middle distance. Structurally, the Fort Union Formation and the Hell Creek Formation under it are composed of stream beds, river deltas and marine lagoon margins that ebbed and flowed across the landscape for tens of millions of years. Intermittent swampy forests laid down dense mats of plant matter, quickly buried in this depositional setting and gradually compressed into soft coal or lignite. The lignite layers are the softest element in these bands of compressed clay. When lignite becomes exposed on the surface the erosion is more or less immediate. A lignite lens is doing very little to protect this ridge from erosion above the Little Missouri. Fort Union lignite from Wibaux County, Montana--note bark fragments. These soft coal seams can be ignited by lightning strikes or wildfires, and they may flame up or smolder for years or decades. A seam burning in the TRNP now has been cooking along for years. These slow fires bake the clay layer above into brick, or scoria. These layers of fairly hard red scoria become cap rocks protecting the soft mudstones beneath from sudden erosion. The whole thing is strangely architectural. "Brick" or scoria cap rock. Loss of the burned lignite layers leads the brick to slump. Another badlands cap rock: weak shale. Other cap rocks include a weak shale, and at the highest point in the south unit of the TRNP the cap rock is a sandstone stream bed deposit. Sandstone concretions lead to the creation of hoodoos. Little hoodoos everywhere. Calling a bluff. The astonishing prairie dogs and bison justified the trip, for sure, but the mudstone-lignite-brick architectural system of the Fort Union badlands is otherworldly. Non-volcanic scoria is a winning concept to this simple mind. It's fascinating to think of this natural structure as an extension of the Cretaceous. The Fort Union Formation extends deeply into Montana, where the Hell Creek Formation surfaces occasionally in Wibaux County. An adventitious local uplift of the Hell Creek near Glendive runs off to the southeast for many miles, and Makoshika State Park on the edge of Glendive exposes the K-T Boundary along with a massive cross-section of the Fort Union. The Yellowstone River has left vast and grandiose monuments here. Makoshika. Gigantic hoodoos. Huddled masses yearning to break free. The Hell Creek Formation is one of the smoking guns for the end of the Cretaceous and the extinction of the dinosaurs. Visitors come for the dinosaurs as much as the scenery. Montana State University's Museum of the Rockies in Bozeman has a world-class display and dinosaur enthusiasts might consider spending a full day in this beautiful museum, wallowing in catastrophic numbers of fresh dinosaur finds, room after room. Meet the locals at the Museum of the Rockies in Bozeman, Mt. Other site-local exhibits include a very good display at the small Dickinson Dinosaur and Badlands Museum, and a noteworthy collection at the Glendive Dinosaur and Fossil Museum. The Glendive museum is Creationist, and I greatly regret not taking a photo of the Noah's Ark diorama showing all the plastic dinosaurs that wouldn't fit on board. But to paraphrase Abraham Lincoln, "Let us cut us a break sometimes." When I was a child my plastic dinosaurs fought my plastic cowboys relentlessly. The title of this fresh series of blogs is "Visiting America" and there is nothing more American than Creationism. Edge of the Badlands. Note chuck wagon and cattle drive in the middle distance. Scenes of the long slow collapse of these Paleocene clay formations would go on to haunt us, butte by butte, for many, many hundreds of miles to come... NEXT BLOG: A FEELING OF ISOLATION