The Central Montana landscape can be a little hypnotic, rising and falling knolls and ridges in various shades of khaki, waving with grass. In human terms, it’s a sea of names: Native American names, settler names, geographical, geological and administrative names, nicknames and local usages—a blanket of names on the landscape, visible and invisible, sometimes secretive.

Deep in this grassland, out on the lone prairie, is the most famous historical name in Montana: Little Big Horn. Over the years, the Battle of the Little Big Horn has bred a torrent of history, fiction, fictional history, film, lecture, essay, legend and myth. It’s not just an American fascination. Most people in the literate world, it’s fair to say, have some awareness of this battle and probably an opinion on it. As a coin of culture or plug-in of connectivity, the Battle of the Little Big Horn is world currency.

Why? It’s small for a battle. U.S. casualties were 268 killed and 55 wounded. Sioux casualties are unknown, but the National Park Service considers 36 to 130 to be a plausible range. Custer lost a battle. The Sioux lost the campaign. The campaign was meaningless, because the Sioux were barely surviving, along with the American bison on which Sioux life depended, a singular horror mainly caused by disease, ecological disaster and hunger. No territory was lost or won in the 1876 campaign; the Little Big Horn is on Crow land, and the Crow were on the U.S. side before and after the battle. But this battle was not relegated to obscurity like other battles in the long cycle of Sioux wars. Little Big Horn became a legend translated into every language, a meme, an elevator button to the Sitting Bull and Custer floor. Entry in the Great Events pantheon began almost as soon as the battle ended. Native American witnesses suggest it was an instant legend for the Sioux as well. But that doesn’t answer “why.” Widespread cultural awareness that “a thing happened” is an effect, not a cause.

In the end I think we have to answer “why” ourselves, and not agree to be merely told why the Little Big Horn fight mattered—though we can easily see that it did matter. The first people on the battlefield after the Sioux did not find a mystery, but mystery soon found them.

Depopulation by pandemic was once again the forerunner of migration and resettlement, as it had been in 17th-century Virginia and Massachusetts. European diseases reached the Great Plains before the first white settlers arrived, as Lewis and Clark saw and recorded. Rarely was the spread of epidemics deliberate, though there is the example of Lord Amherst in King Philip’s War of 1675-78.

For those of us who might not have access to oral traditions or other forms of heritage subtly linking the present to the past's deep time, no written record exists of the original state of the Plains Indians before the first smallpox waves. We have only flat two-dimensional ideas of that society. Even less likely are we to reimagine the Plains Indians before the adoption of the horse, re-introduced to North America by Spanish colonization. Reconstruction of those lost societies is a job for archeologists and historical ethnographers. By 1876, the year of the Little Big Horn battle, the Native American population had been reduced to remnant bands, survivors of a world-ending plague. The settlers did not worry about this. They died of the same diseases themselves, though not as readily. To them, Indians were part of nature and not the most convenient part. A European-American cultural script for Native Americans was already in place, sculpted by writers like James Fenimore Cooper for the literate general audience.

Why an 1876 campaign, and why Custer? In 1874, the Black Hills belonged to the Sioux, affirmed and reaffirmed in the Laramie treaties. However, persistent rumors of gold led Colonel George Armstrong Custer to invade the Black Hills with a 1,000-strong cavalry column, reaching modern Custer, Wyoming and finding modest quantities of gold. Like Bannack and Virginia City the decade before, thousands of miners and profiteers headed for the Black Hills. The rush led to massive finds of raw gold in the northern Black Hills around Deadwood. There was no U.S. theory that the Sioux could own their own gold. The events started by Custer’s treaty violation soon dispossessed the Sioux. Treaty violations called Federal authority into question, not least the reservation system. It’s hard to be more succinct than Wikipedia about this. “Among the Plains Tribes, the long-standing ceremonial tradition known as the Sun Dance was the most important religious event… Towards the end of spring in 1876, the Lakota and the Cheyenne held a Sun Dance that was also attended by a number of "Agency Indians" who had slipped away from their reservations. During a Sun Dance around June 5, 1876, on Rosebud Creek in Montana, Sitting Bull, the spiritual leader of the Hunkpapa Lakota, reportedly had a vision of "soldiers falling into his camp like grasshoppers from the sky." At the same time US military officials were conducting a summer campaign to force the Lakota and the Cheyenne back to their reservations, using infantry and cavalry in a so-called "three-pronged approach".”

Not all Plains tribes and leaders responded the same way to the complicated situations they were faced with. These societies, whose social and cultural orders were fully disrupted within living memory, were trying to survive as best they knew. They were warrior societies in permanent mutual conflict. We might think of the Plains Chieftains as somewhat like the heroes of the tribal Greeks in the Iliad, autarchs whose authority rested on heroic charisma. The Plains Indians knew the relationship between power and violence. Some of the lands declared to be Sioux by U.S. treaty belonged to other tribes. The Lakota, for instance, had a history of ignoring Crow boundaries and the Crow had asked for U.S. cavalry help. It was no coincidence that the climax of the campaign occurred on Crow territory. The Crow, Arikawa and others sided with the U.S. and fought in the 1876 campaign as guides and as auxiliary cavalry—a power-based decision.

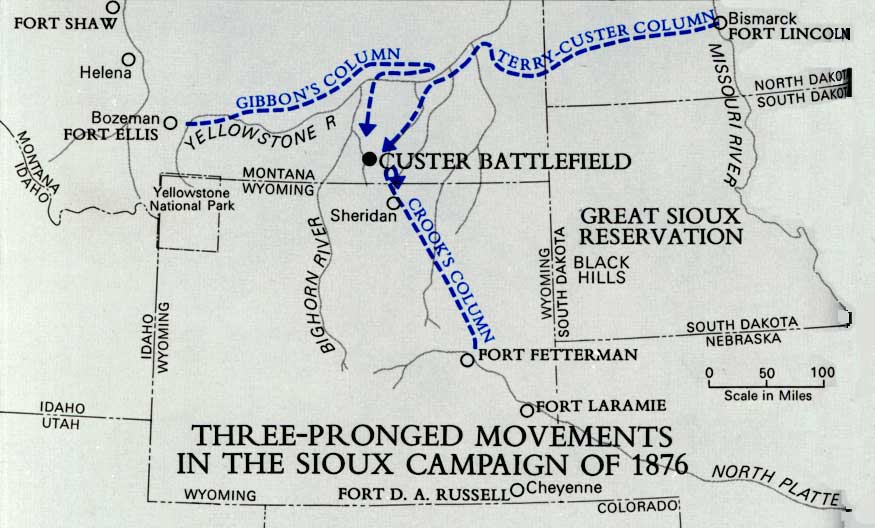

The army deployed three small columns under Brigadier-Generals Crook and Terry and Colonel Gibbon, including hundreds of Crow and other Indians as scouts and allied cavalry. Colonel Custer commanded Terry’s striking force. The combined number of troops in the three columns was comparable to a Civil War-era brigade, minus the artillery. Many were tied up in supply lines and forts. The roadless area over which these three columns campaigned was quite a bit larger—very much larger—than General Grant’s entire theater of war back in Virginia. The map below visualizes the territorial scope and time frame of the Sioux Wars.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_the_Little_Bighorn#/media/File:The_Lakota_Wars_(1854-1890)._The_battlefields_and_the_Lakota_treaty_territory_of_1851_(circa.).png

Communication between the Federal columns was incredibly difficult. The Sioux proved hard to locate, but on June 17, 1876, in fulfillment of Sitting Bull’s prophesy, Crook’s column found Crazy Horse and his Lakota and Cheyenne fighters on the Rosebud River. Several hours of hard fighting later, Crook’s Crow allies probably saved Crook’s column from disaster by enabling surrounded troopers to get out. Crazy Horse’s forces then withdrew, and General Crook also retreated. The Battle of the Rosebud knocked Crook out of the fight.

Crazy Horse then joined Sitting Bull’s great gathering of the tribes on the Little Big Horn, an encampment celebrating a major religious revival, ceremonially trying to summon the aid and guidance of powers they understood from the universe around them, powers they were familiar with as manifestations of the divine. Calling fervently on the spiritual beliefs of the past in a last-ditch Appeal to Heaven is a natural social response to existential threat.

Battlefields are the forensic remains of old battles, and speak volumes about what really happened. Generations of scholars, historians and other enthusiasts have spilled ponds of ink about Custer, the Sioux and the Battle of the Little Big Horn. Controversies, theories and reconstructions brew along enthusiastically to this day. There are dedicated specialists in Little Big Horn Studies. The battlefield itself contributes to this fascination. Even if we ignored the many-faceted iconographic status of the Battle of the Little Big Horn in American culture, all the roles the battle has played in the American imagination, and even if we ignored the real causes, purport and issue of the battle, the jewel-like mysteries of the battlefield itself would still remain.

There are no definitive versions of the Battle of the Little Big Horn. Richard A. Fox’s Archaeology, History, and Custer's Last Battle: The Little Big Horn Reexamined (University of Oklahoma Press, 2015) comes park-ranger-recommended as a physical survey of the battlefield and its artifacts. The forensic analysis of archeologically-recovered cartridge cases tells a non-theoretical tale. The shell casings discriminate between cavalry and Sioux shooters and can even trace the movements of some of the gunmen across the battlefield.

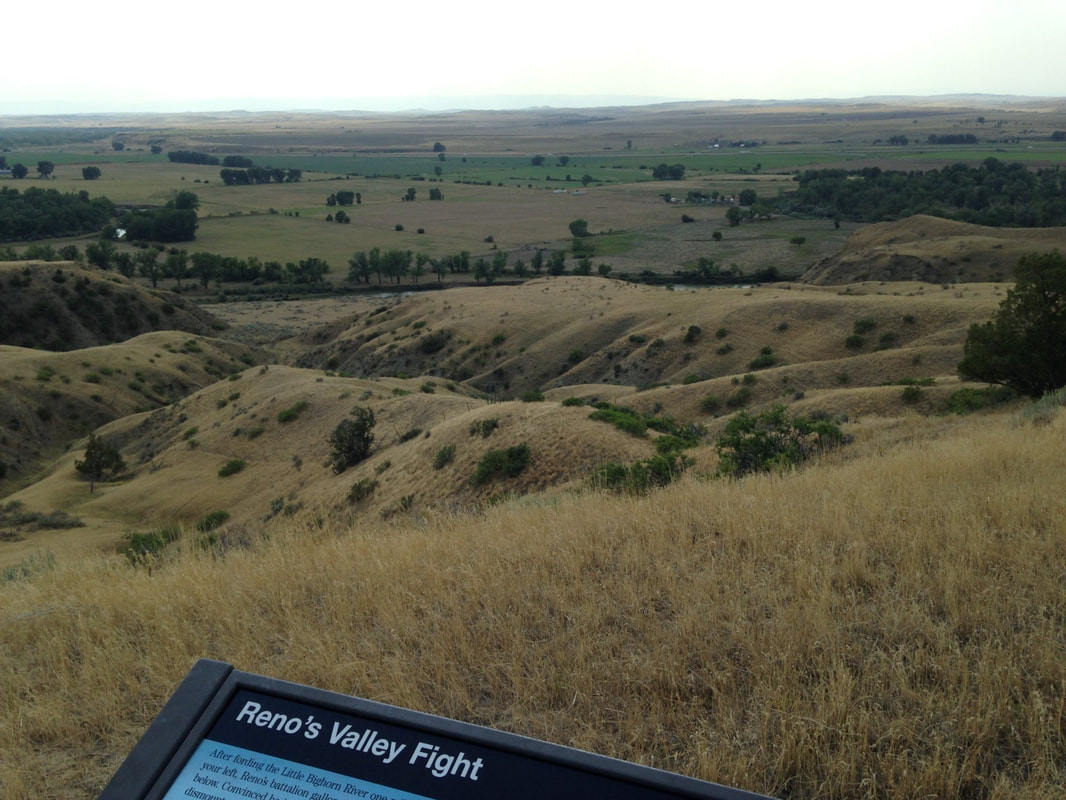

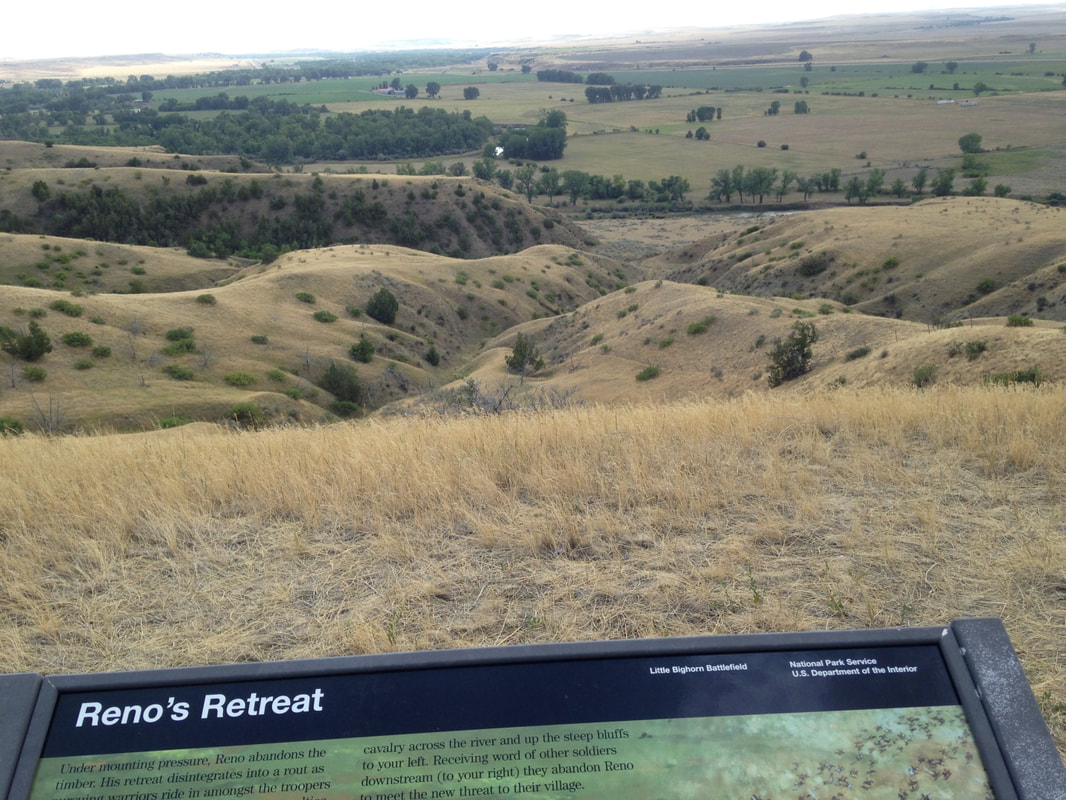

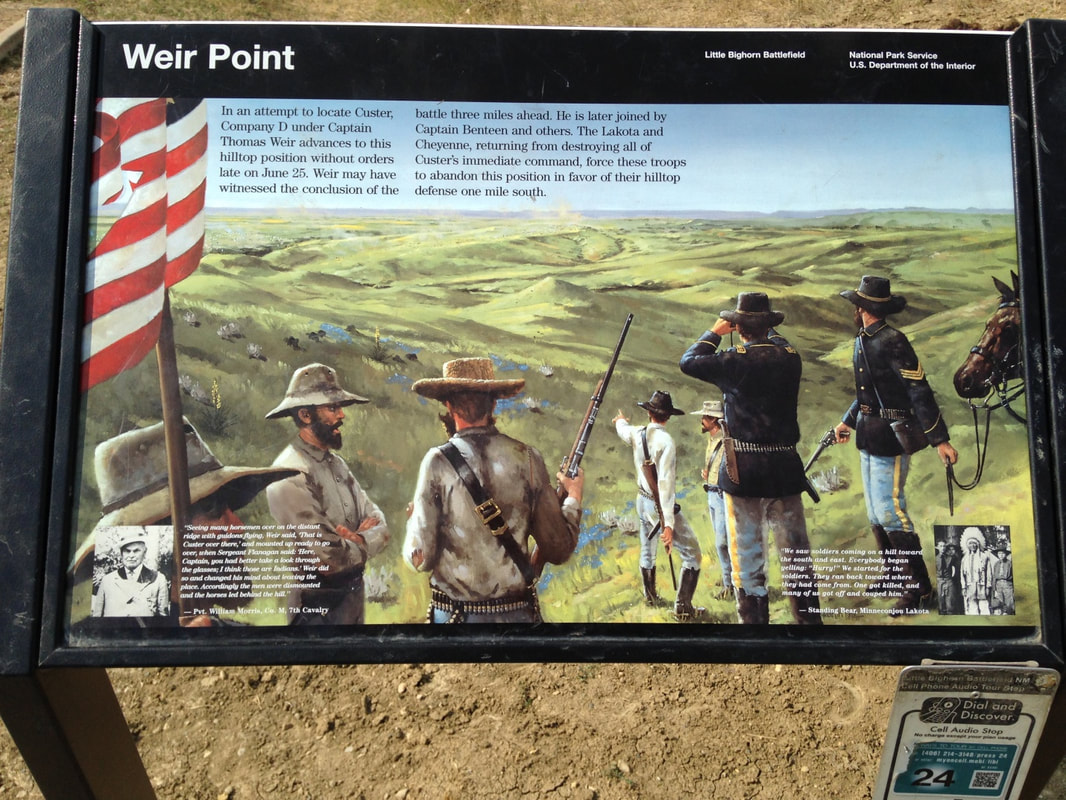

Custer had a large staff and 12 companies at his disposal, a bit over 40 men per company, with 35 Indian scouts, six Crow and the rest Arikawa, for a total of approximately 647 troopers and scouts. One company guarded the supply train. Of the remaining 11 companies, Custer assigned three to Captain Frederick Benteen and three to Major Marcus Reno. Benteen was sent to scout an open flank, and Reno was ordered to attack the southern end of the Sioux encampment. Custer retained Companies C, E, F, I and L.

Before he divided his companies, Custer had been told that this was the largest Indian encampment his scouts had ever seen. No doubt it was. With an immensely charismatic leader like Sitting Bull seeking supernatural intervention in a moment of utmost crisis, the Little Big Horn Encampment may have contained nearly all of the last free Sioux. We may as well ask who wasn’t there when Custer arrived.

It’s interesting to learn what the Sioux were shooting with. The bow, the lance and the club remained the main weapons of many Sioux, but archeological shell casings and forensics determined the minimum number of different kinds of rifles fired at various points on the battlefield. Fox’s chart (p. 78) in Archeology, History, and Custer’s Last Battle shows 27 Sharps 50-cal. rifles and 62 Henry 44-cal. rifles on Custer’s part of the battlefield, among a large miscellany of other popular Civil-War-era rifles and pistols. A lot of the rifles carried by the Sioux in 1876 were heavy calibers suitable for buffalo, and the balance of firepower may have been on their side at critical moments.

Archeological evidence suggests Custer pulled back to what is now called Calhoun’s Ridge, where he positioned Companies I and L behind a C Company skirmish line. Custer then rode with his large staff, pack of relatives, and Companies E and F around the east side of what would come to be known as Custer Hill, across the area where the Visitor Center, National Veterans Cemetery, and parking lot are now, and then down to the stream bed of the Little Big Horn. Traditionally the Visitor Center and National Cemetery were considered to be off the active part of the battlefield, but cartridge case finds and the dead body of Custer’s newspaper correspondent show that at least some of Custer’s staff got as far as the creek below the cemetery. There they may have finally found the hard-to-spot upper end of the Sioux encampment. However, the entire attack had already failed.

During Custer’s excursion to the top of the Sioux camp, C and L Companies were driven from Calhoun’s Ridge to Calhoun’s Hill, rapidly surrounded, and overrun. Archeologically by shell casings and by the accounts of Reno and his officers, who counted the shell cases they saw in 1876, the collapse of this position involved a considerable expenditure of cartridges and the heaviest shooting of the Custer fight. Chief Walks White, or Lame White Man, was killed starting this attack, and here the Sioux suffered most of their casualties, based on oral histories. Warriors led by Gall, Two Moons, and Crow King finished off C, I and L Companies mostly with hand weapons, chasing them “like buffalo,” except for the half dozen or so on the fastest horses making off for the other side of Custer Hill.

Horses can move pretty fast, but time was now gone. As Fox reconstructs events from the archeology, Custer, his staff and Company F broke for the high ground of Custer Hill. Most of Company E split off, possibly to block mounted warriors coming out of the encampment onto Custer Hill by way of Deep Ravine. E Company was destroyed at once. A handful of F Company, Custer and staff got as far as the markers where they fell. The entire Custer fight took roughly half an hour and the Custer Hill climax may have been over in minutes. By this reading, Custer died in mid-maneuver as his command disintegrated around him.

The next day, June 27, Reno's survivors reached the scene of the Custer fight. Captain Benteen later reported:

"I went over the battlefield carefully with a view to determine how the battle was fought. I arrived at the conclusion I [hold] now—that it was a rout, a panic, until the last man was killed ... There was no line formed on the battlefield. You can take a handful of corn and scatter [the kernels] over the floor, and make just such lines. There were none ... The only approach to a line was where 5 or 6 [dead] horses found at equal distances, like skirmishers [part of Lt. Calhoun's Company L]. That was the only approach to a line on the field. There were more than 20 [troopers] killed [in one group]; there were [more often] four or five at one place, all within a space of 20 to 30 yards [of each other] ... I counted 70 dead [cavalry] horses and 2 Indian ponies. I think, in all probability, that the men turned their horses loose without any orders to do so. Many orders might have been given, but few obeyed. I think that they were panic stricken; it was a rout, as I said before."

I hope that was a refreshing account of an old battle, but it occurs to me nothing in it says why it matters. But we know it did.

Little Big Horn is a tangibly spiritual space, not just the site of an incident in the Great Sioux War. The nature of places has never been something language captures well. The ancient Greek belief in daimons of place or landscape remains compelling to me.

Reno’s command had already left a trail of graves across the battlefield before they reached Calhoun’s position and the first bodies. All the bodies on the battlefield had been mutilated, which the ancient Sioux did both for revenge and to release the angry spirits. Also everything of the least value or use had been stripped and carried off. One witness remarked that no horse equipment of any kind was left behind, “not even a strap.” The bodies had been in the sun long enough to swell up, and most were unrecognizable. The troopers buried them where they lay, in very shallow graves marked by stakes, sometimes scooping the dirt over the body from both sides in a low mound, and sometimes covering the barely-scraped graves with brush. They had a long string of burials to perform, all the way to Custer Hill and Deep Ravine, and they were exhausted and shot up and tending to over a company’s worth of wounded. It wasn’t the best job.

A year later, in 1877, the army mounted a reburial expedition. The graves were exhumed and re-interred, and the officers’ remains were taken back for their families to dispose of, including five members of the immediate Custer family. But this wasn’t enough. Another expedition to repeat the performance and further improve the Little Big Horn burials was sent in 1879. That wasn’t enough either. A more fully equipped expedition in 1881 moved all the relocatable remains to a mass grave at the top of the hill, and installed a granite obelisk. They also re-marked the original grave sites. Obviously that, too, wasn’t nearly enough, and in 1890 Captain Owen Sweet and company arrived with 246 individual marble markers for the original grave sites as best he could determine them. To quote Fox, “…Sweet incorrectly placed on Custer’s battlefield 44 markers intended to memorialize Reno’s dead.”

Sweet’s placements, when you’re on the field, subtly tattoo the landscape. They’re artistically placed in an Aesthetic Era fashion and we are reminded that an 1890 cavalry captain is a civilized man. He stayed within the constraints of the original burials but counted depressions as former graves. Thus, where dirt had been dug out from both sides to mound the body in a shallow grave, Sweet counted that as two graves. Twin graves appear prominently here and there. In the Ruskin-inspired esthetic appropriate to the period, the overall pattern of placements would be unthinkable without these twinned stones. In a way they mark the original locations of the worst-buried people and in another way they save the whole pattern from mere naturalistic formalism. The Spirits love these dual meanings. The deeper meaning goes past spirit. The pattern of the grave markers on the Little Big Horn battlefield is not exactly an accident. Contrapuntally we can ask whether the markers do or do not amount to coincidence. If we go with coincidence as an explanation of the pattern, then it’s a large one.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed